Republican lawmakers in Florida are working on a bill to require former felons to pay fees and fines before having their voting rights restored, prompting criticism from those who say it would undermine a new amendment that allows more than a million former felons to vote again.

Supporters of the bill contend that it is meant merely to resolve questions over how to put Amendment 4, which voters approved in November, into practice.

But voting rights advocates say the bill would unfairly punish those who are unable to pay and undermine the central objective of the amendment: ending permanent disenfranchisement.

Democratic state Rep. Adam Hattersley labeled it “blatantly unconstitutional as a poll tax,” a reference to the fees used to keep African-Americans from voting in the South starting in the 1890s. (African-Americans are disproportionately affected by felony disenfranchisement, though the majority of Floridians with felony convictions are white.)

Organizations are already lining up to file lawsuits against the bill if it becomes law.

Democrats are watching closely because many believe had ex-felons been allowed to participate in 2016, their votes would have wiped out President Trump’s 113,000-vote victory in Florida.

The implication is the successful amendment will dramatically benefit Democrats throughout the state in 2020.

But political scientists who study election administration and have written extensively on felon disenfranchisement agree Florida’s previous attempt at a similar, but smaller, reform suggests that a blue wave is unlikely.

The state restored the vote to a small group of ex-felons from 2007 to 2011 under then-governor Charlie Crist.

Crist restored the right to vote to about 150,000 ex-felons convicted of less serious offenses. (Gov. Rick Scott rescinded the policy in 2011, but the 150,000 ex-felons remain eligible to vote.)

By combining information contained in public records, Vox assessed how often these 150,000 individuals vote and which party they register with.

The conclusion: Ex-felons vote at low rates. And when they do, there is no strong partisan lean.

One thing that limits the electoral impact of restoring ex-felons’ voting rights is that they turn out at particularly low rates.

To demonstrate this, Vox looked to the population of ex-felons who were restored the right to vote under Crist and calculate what share voted in 2016.

Just 16 percent of black and 12 percent of nonblack ex-felons voted.

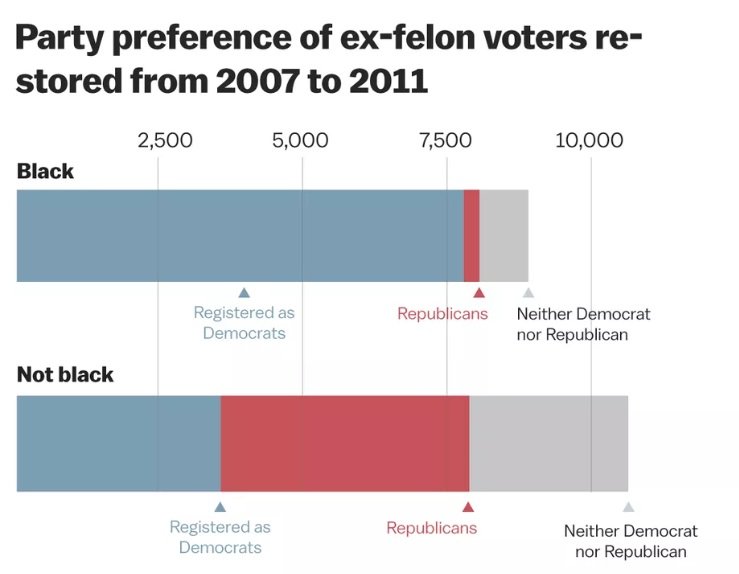

The potential electoral impact for 2020 is further limited by the fact that the ex-felons who do vote are not politically uniform.

While black voters within this population overwhelmingly register with the Democratic Party (87 percent), nonblack voters within this population were more likely to register as Republicans (40 percent) than as a Democrats (34 percent).

The fact that 26 percent of the remaining nonblack voters affiliate with neither party suggests that their votes may not reliably be cast for either party.

According to the Sentencing Project, there were 1,487,847 ex-felons in Florida who were unable to vote during the 2016 election, of which about a quarter, or 418,224, were black.

Even though black ex-felons are overwhelmingly Democratic, the racial breakdown reveals that there are many more nonblack ex-felons, whose political preferences are much less certain.

Although people do not always vote consistent with their party of registration, we can approximate the electoral impact by assuming that they would.

Specifically, we multiply the estimated disenfranchised population first by the turnout rate and then by the party registration rate for both black and nonblack individuals.

Had all ex-felons been eligible to vote in Florida in 2016, we estimate that this would have generated about 102,000 additional votes for Democrats and about 54,000 additional votes for Republicans, with about an additional 40,000 votes that could be cast on behalf of either party.

It’s likely Trump still would have carried the state and its electoral votes.

Meanwhile, the number of Puerto Ricans eligible to vote in Florida now equals that of the politically powerful Cuban-American population, according to a Pew Research Center report.

The 6.2 percent increase of Hispanic registered voters since 2016 also more than tripled that of the 1.8 percent growth of all new registered voters.

Overall, more than 2.1 million Hispanics in Florida are registered to vote in Florida, now making up more than 16 percent of all registered voters.

The number of island-born Puerto Ricans eligible to vote in Florida has grown by about 126,000, or 30 percent, since 2016.

In the aftermath of Trump’s handling of Hurricane Maria, and his constant bickering with Puerto Rico officials, Democrats may find a bigger voter goldmine here than placing all hope of flipping Florida blue on ex-felons.