It was 1860, Chicago, Illinois. One-term former congressman Abraham Lincoln arrived at the Republican National Convention a dark horse for the nomination. In fact, only one person in America at that point – Lincoln himself – thought he could be the Republican nominee.

Lincoln knew the odds were small, but he understood party politics inside and out.

In fact, the previous December Lincoln had watched as his likely opponents bickered over where to hold the upcoming Republican convention. New York, Ohio and Missouri were all in the mix, but each were home of a “favorite son” candidate. Lincoln, who did not make his own ambition known publicly, wrote to a member of the selection committee, Norman Judd, and suggested Illinois be chosen as a “neutral” location.

The idea was accepted.

Without them knowing, Lincoln had steered the big party to Chicago. His own backyard.

William Seward, former governor of New York and a U.S. Senator, came into the convention as the clear front-runner. Just about everyone thought the nomination was his to lose, he had built a huge delegate lead. But, as per the rules, he did not have enough to clinch the nomination.

There’s this thing about party politics. It’s a game of negotiation, promises and coalitions. And no one understood back slapping and handshakes better than the country lawyer from Illinois.

Downplaying his interest in being the nominee to the end, Lincoln decided to remain in Springfield. “I am a little too much a candidate to stay home, and not quite enough a candidate to go,” he said.

Arriving at the convention, Lincoln’s inner-circle went to work first on wavering delegates who thought Seward could not win key battleground states. Then they quietly started mentioning Lincoln as the alternative, and in doing so, created an atmosphere where Lincoln’s name seemed to be pushed by the delegates themselves.

Brilliant.

Brilliant.

Notice at no time did Lincoln, or his team, complain about party politics. Quite the contrary. They understood the rules and set out to win by using them.

Within state delegations there was infighting. Big states like Pennsylvania were feuding internally. Lincoln described his position within the party as “neither on the left wing, nor the right, but very close to dead center.” An alternative candidate for everybody.

Several Republican heavyweights, like Ohio Gov. Salmon Chase, believed Seward could not win a majority of delegates. But in representing their own cliques, they failed to broaden their own chances for the nomination.

Lincoln’s team spent the first hours at the convention chipping away delegates. First a few from New England, then Indiana, then Pennsylvania. “We are laboring to make you the second choice of all the delegations we can, where we can’t make you first choice,” supporter N.M. Knapp wrote to Lincoln. “We are dealing tenderly with the delegates taking them in detail and making no fuss.”

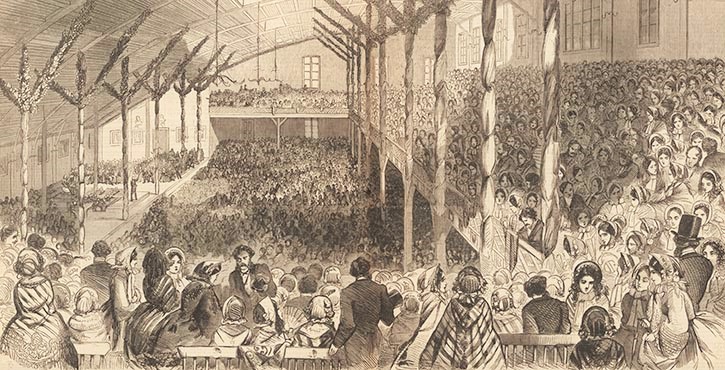

The convention was being called by the press “the greatest show on earth!” Tens of thousands traveled from across the country to be there. One of the advantages of having the convention in Lincoln’s backyard was being able to easily pack the hall. When supporters of Seward took to the streets to parade, Lincoln’s managers printed out counterfeit tickets and packed the convention hall with “shouters for Abe!”

That’s some shady party politics right there. But it worked.

All of a sudden Lincoln’s presence at the convention became well known to everyone.

Lincoln’s team now had one objective: Convince the majority that Seward was not electable come fall. And enough delegates were beginning to believe it.

When Lincoln’s name went into nomination his supporters were ready. “A thousand steam whistles, ten acres of hotel gongs, a tribe of Comanches, headed by a choice vanguard from pandemonium,” wrote one spectator.

Seward led the first ballot 173 ½ to 102. But you needed 263 to win the nomination. Seward’s supporters were shocked. He had a majority of the delegates and some believed that entitled him to the nomination. After all, he had been the presumed nominee for months.

But that’s not how the game works.

On the second ballot, delegates from Pennsylvania, no longer bound by loyalty to Seward, flipped to Lincoln and he closed to within three and a half votes of Seward 184 ½ to 181.

“I shall be nominated on the next ballot!” Seward told supporters. Inside the hall Seward’s team became visibly angry. They felt the nomination was somehow being stolen from them. But Lincoln’s team knew the rules and were demonstrating remarkable patience.

With the convention now equally split, the momentum favored Lincoln. He had made far fewer enemies than Seward, and his tactic of convincing delegates that only he could win in November was working.

On the third ballot, with tens of thousands of people packed into the Wigwam in Chicago looking on, 15 critical delegates from Ohio flipped to Lincoln. He had finally overtaken Seward and reached 231 ½ delegates. But he was still 1 ½ votes short of victory.

There was a pause. For about ten seconds there was silence as delegates pondered yet another round of voting.

Then, the chairman of the Ohio delegation stood and announced four more of his delegates had flipped to Lincoln.

“A profound silence fell upon the wigwam,” one journalist wrote. “Then the delegates rose to their feet applauding rapturously, the ladies waving their handkerchiefs, the men waving and throwing up their hats by the thousands, cheering again and again.”

Abraham Lincoln, on the third ballot and after months of silent preparation, was the nominee of the Republican Party.

“Had the convention been held in any other place, Lincoln would not have been nominated,” said his longtime friend Gustave Koerner.

In the end, Lincoln’s early knowledge of party politics, and not his criticism of it, allowed him to outwit and outlast his opponents.

Seward did not abandon the Republican Party after his defeat, nor did he denounce the convention. Instead, he campaigned for Lincoln throughout the fall and would later become his trusted Secretary of State.

As for Lincoln, he would become perhaps the greatest president in American history.