Donald Trump is running the American government like a business – or, if we’re being precise, like The Godfather.

Trump’s penchant for asking himself, “What would Roy Cohn advise John Gotti to do?” has been clear for some time.

Cohn was America’s most loathed, yet socially successful, defense attorney who had vaulted to infamy in the 1950s while serving as legal counsel to Senator Joseph McCarthy.

Cohn helped McCarthy wage witch-hunts on the “deep state” – the State Department, Voice of America, and the Army.

When McCarthy was finally censured, in 1954, Cohn was thought to be finished, too.

He moved back to New York City and joined a law firm, but instead of fading into obscurity, Cohn became a socialite with a roster of high-powered, famous, pious, and allegedly murderous clients.

After graduating from the Wharton School and successfully avoiding deployment to Vietnam, Trump joined the family real-estate business and in 1971, moved to a studio apartment on the Upper East Side.

He wasted no time beginning his social ascent.

“One of the first things I did was join Le Club,” he wrote in his 1987 book The Art of the Deal, “which at the time was the hottest club in the city and perhaps the most exclusive—like Studio 54 at its height. Its membership included some of the most successful men and most beautiful women in the world.”

Le Club, Trump wrote, “turned out to be a great move for me, socially and professionally.”

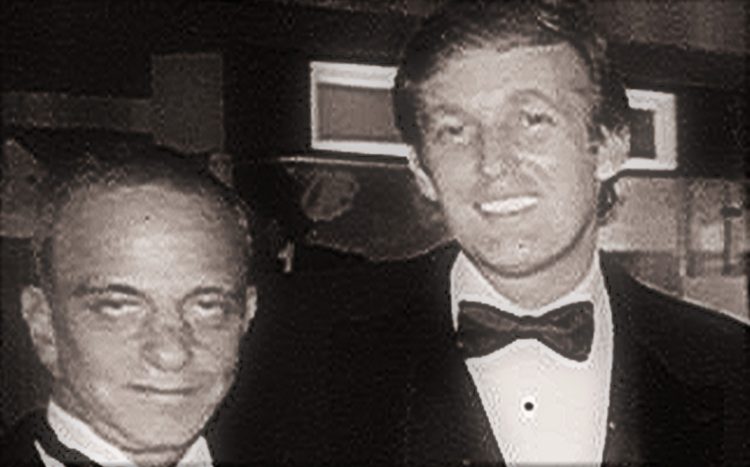

Cohn, who represented Le Club, became Trump’s lawyer.

And Trump thought highly of his controversial tactics.

“If you need someone to get vicious toward an opponent, you get Roy,” he was quoted as saying by the Associated Press. “People will drop a suit just by getting a letter with Roy’s name at the bottom.”

The friendship Trump and Cohn forged would provide the foundation for Trump’s eventual presidential campaign.

Trump’s “Greatest Mentor” was Red-Baiting Aide to Joseph McCarthy and Attorney for NYC Mob Families Roy Cohn.

The depth of their relationship didn’t end with Cohn’s attack-dog defenses of his client.

Cohn, in his own words to the New York Times, was “not only Donald’s lawyer, but also one of his close friends.”

It was Cohn, the mob lawyer, who helped transform him.

Critics have taken note of Trump appearing to support omertà—the Cosa Nostra’s signature code of silence—and how his behavior recalled Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano, the mob associate who brought down Gotti.

In his book A Higher Loyalty, fired FBI director James Comey went so far as to suggest Trump’s demand for personal fealty was like “Sammy the Bull’s Cosa Nostra induction ceremony.”

Later, in his first interview after wrapping up a 17-year prison sentence for drug dealing, Gravano himself responded to Comey, giving Trump a stamp of approval: “The country doesn’t need a bookworm as president,” he said. “It needs a mob boss.”

Michael Cohen, Trump’s longtime lawyer and fixer, went from saying he would take a bullet for his boss, to testifying against him in Congress.

Last August, Trump said of the possibility that Michael Cohen would cooperate with Robert Mueller’s investigation, “I know all about flipping. It should almost be illegal.”

Around that same time, Trump insisted that his White House counsel, Don McGahn, was not a “a John Dean type ‘RAT’” — a reference to President Nixon’s lawyer, who testified (truthfully) about his boss’s attempts to obstruct justice.

And Trump has repeatedly argued that the U.S. attorney general’s primary responsibility is to demonstrate unflinching loyalty to the president, as though the federal government was the Mafia and Trump its godfather.

Thus, Robert Mueller’s investigation finally confirms the leader of the free world thinks like a mobster, with behavior indistinguishable from that of a mafioso.

The Trump presidency long has been an exercise in normalizing extraordinary behavior, with Trump repeatedly stretching the limits of what is considered appropriate conduct by the nation’s chief executive.

The Mueller report provides a damning portrait of Trump and those around him for actions taken during the 2016 campaign and while in office.

The 448-page document is replete with evidence, of repeated lying by public officials and others (some of whom have been charged for that conduct), of the president urging not to tell the truth, of the president seeking to shut down the investigation, of a Trump campaign hoping to benefit politically from Russian hacking and leaks of information damaging to its opponent, of a White House in chaos and operating under abnormal rules.

It shows a White House where officials sometimes — but not always — resisted the president’s more nefarious orders and concludes that Trump was not able to influence the investigation as much as he wished because advisers declined to carry out some of those orders.

It also suggests, despite his many claims to the contrary, that Trump felt vulnerable to an investigation.

When informed just months after taking office that a special counsel was to be appointed, Trump exclaimed that it would mean “the end of my presidency.”

The Mueller report provided overwhelming evidence of how the Russians carried out their effort to interfere with the election.

The details in the report buttress the earlier findings by the U.S. intelligence community of Russian meddling with the intent of helping Trump defeat Hillary Clinton.

It is a finding the president has never fully embraced, repeatedly equivocating as to whether Russians were responsible, for reasons that remain unclear.

What is clear, however, are the Tony Soprano moments.

For instance, in June 2017, Trump directed White House counsel Don McGahn to have Robert Mueller fired.

McGahn then let it be known that he would resign before carrying out such an order.

By the following January, the New York Times had gotten wind of that conversation.

And when the paper’s story hit newsstands, Trump ordered McGahn to dispute the report.

McGahn refused to lie.

In a tense Oval Office meeting, Trump further pressured the White House counsel to dispute the Times story — and then asked McGahn about his recent conversations with Mueller’s office.

A very mobster-esque exchange ensued:

“The President also asked McGahn in the meeting why he had told Special Counsel’s Office investigators that the President had told him to have the Special Counsel removed. McGahn responded that he had to and that his conversations with the President were not protected by attorney-client privilege. The President then asked, “What about these notes? Why do you take notes? Lawyers don’ t take notes. I never had a lawyer who took notes.” McGahn responded that he keeps notes because he is a “real lawyer” and explained that notes create a record and are not a bad thing. The President said, “I’ve had a lot of great lawyers, like Roy Cohn. He did not take notes.”

In November 2017, Trump’s former national security adviser Michael Flynn started cooperating with the special counsel, and withdrew from a joint defense agreement he’d struck with the president.

Hours after Trump learned of Flynn’s decision, his personal lawyer left a voice-mail for Flynn’s counsel:

I understand your situation, but let me see if I can’t state it in starker terms … [I]t wouldn’t surprise me if you’ve gone on to make a deal with … the government … [I]f … there’s information that implicates the President, then we’ve got a national security issue … so, you know … we need some kind of heads up. Um, just for the sake of protecting all our interests if we can …. [R]emember what we’ve always said about the President and his feelings toward Flynn and that still remains.

Flynn’s counsel then informed the president’s attorney that it could not provide Trump with such a “heads up.” Trump’s counsel responded by warning that he would inform the boss of Flynn’s “hostility.”

“The President’s personal counsel said that he interpreted what they said to him as a reflection of Flynn’s hostility towards the President and that he planned to inform his client of that interpretation. Flynn’s attorneys understood that statement to be an attempt to make them reconsider their position because the President’s personal counsel believed that Flynn would be disturbed to know that such a message would be conveyed to the President.”

In a broader sense, a key part of why it’s so appealing to see Trump through the Mafia lens is just that—his use of language.

Last August, the Times published yet another piece analyzing his diction, tracing it back to the Brooklyn political machine he was surrounded by growing up.

The paper cited his comfortability with shady businessmen and mob-backed public officials (“raffish types with their unscrupulous methods,” like his McCarthyite mob lawyer Cohn), and called attention to the time he defended Paul Manafort by referencing Al Capone.

“Using words like ‘flip’ or ‘rat,’ it’s a defensive move from somebody who generally has guilt to bear,” said Christian Cipollini, who has written numerous books on the mob. “But I will say this, too: Anyone who built things in the 1980s in New York, they were going to deal with the mob whether they wanted to or not. So, however conscious it is, if you’re sitting on the Hill and saying those words, to everyone you’ve fired or who you think has betrayed you, you’re something of a mob boss.”

“Are we just so stunned right now,” Cipollini asked, rhetorically, “that we’re finally seeing what’s been in front of our faces?”

Long before the release of the report, Trump had effectively politicized the Mueller investigation. For many of Trump’s loyalists, retribution is the next order of business.

Trump said, “This hoax … should never happen to another president.” His reelection campaign sent out an email Thursday headlined, “Time to Turn the Tables,” saying it was time “to investigate the liars who instigated this sham investigation.”

The question for voters in November 2020 is what they want of and expect from a president.

The inspiration of a Franklin D. Roosevelt. The heroism of a Dwight D. Eisenhower. The vigor of a John F. Kennedy. The optimism of a Ronald Reagan.

Or the lies, deceit, anger and threats of The Godfather.