Senator Elizabeth Warren entered the 2020 race with expansive plans to use the federal government to remake American society, pressing to strip power and wealth from a moneyed class that she saw as fundamentally corrupting the country’s economic and political order.

She exited today after her avalanche of progressive policy proposals, which briefly elevated her to front-runner status last fall, failed to attract a broader political coalition in a Democratic Party increasingly, if not singularly, focused on defeating President Trump.

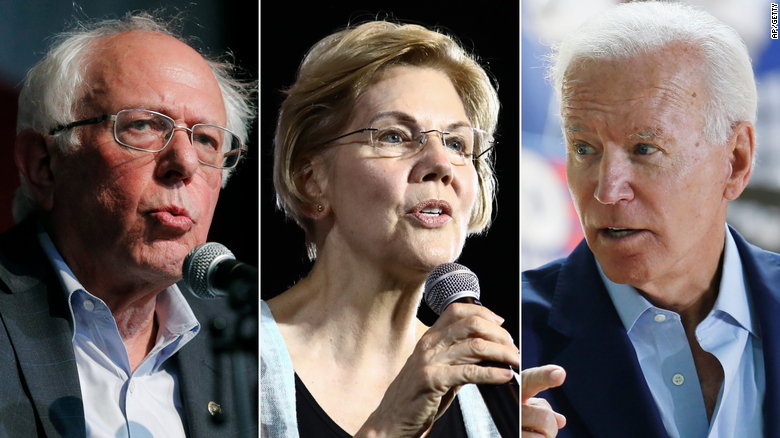

Her departure means that a Democratic field that began as the most diverse in American history — and included six women — is now essentially down to two white men: former Vice President Joe Biden. and Senator Bernie Sanders.

Warren said that from the start, she had been told there were only two true lanes in the 2020 contest: a liberal one dominated by Sanders, 78, and a moderate one led by Biden, 77.

“I thought that wasn’t right,” Ms. Warren said in front of her house in Cambridge as she suspended her campaign, “But evidently I was wrong.”

Though her vision energized many liberals — the unlikely chant of “big, structural change” rang out at her rallies — it did not find a wide enough audience among the party’s working-class and diverse base.

Now her potential endorsement is highly sought, and both Sanders and Biden have spoken with her in the days since Super Tuesday losses sealed her political fate, though she revealed precious little of her intentions on Thursday.

“I need some space around this,” she said.

Warren’s impact on the race was far greater than just the outcome for her own candidacy. Her policy plans drove the agenda.

She effectively pushed former Mayor Michael Bloomberg, a centrist billionaire, out of the race with a dominant debate performance last month.

And her ability to raise well over $100 million and fully fund a presidential campaign without holding high-dollar fund-raisers demonstrated that other candidates, beyond Sanders and his intensely loyal small-dollar donors, could do so in the future.

Warren’s political demise was a death by a thousand cuts, not a dramatic implosion but a steady decline.

In the fall, most national polls showed that Warren was the national pacesetter in the Democratic field.

By December, she had fallen to the edge of the top tier, wounded by an October debate during which her opponents relentlessly attacked her, particularly on her embrace of “Medicare for all.”

She invested heavily in the early states, with a ground game that was the envy of her rivals.

But it did not pay off: In Iowa, where she had bet much of her candidacy — she had to take out a $3 million line of credit before the caucuses to ensure she could pay her bills in late January — she wound up in a disappointing third place.

Warren slid to fourth in New Hampshire and Nevada, and to fifth in South Carolina.

By Super Tuesday, her campaign was effectively over — with the final blow losing her home state, Massachusetts.

The California results strikingly laid bare the demographic cul-de-sac her candidacy had become as Warren struggled to win over voters beyond college-educated white people, in particular white women.

She was poised to win delegates in only a handful of highly educated enclaves: places like San Francisco, Santa Monica and West Hollywood.

Though the campaign failed to generate the widespread backing necessary to win the nomination, Warren retained a core of fierce loyalists dedicated to her promise of wholesale change.

Her selfie lines were filled with well-wishers — young girls seeking her trademark pinkie promise (“I’m running for president because that’s what girls do”), cutouts of Warren’s likeness, and tattoos of her adopted slogan: “Nevertheless, she persisted.

When her staff gathered today, many were clad in liberty green, the color her campaign adopted to symbolize its togetherness.

“One of the hardest parts of this is all those pinkie promises,” a visibly emotional Warren said, describing the “trap” of gender for female candidates.

“If you say, ‘Yeah, there was sexism in this race,’ everyone says, ‘Whiner!’” Warren said. “If you say, ‘No, there was no sexism,’ about a bazillion women think, ‘What planet do you live on?’”

Before her exit, Warren accumulated the second-largest number of Democratic delegates of any woman to run for president in history, behind only Hillary Clinton, the 2016 nominee.

The party’s left lane is now clearer for Sanders.

His supporters and other progressives have spent the last two days gingerly reaching out to Warren’s orbit and plotting in private conversations about how to keep the two liberal standard-bearers aligned.

In January, Sanders and Warren clashed in a deeply personal way after she confirmed a report that in a private meeting before the campaign began, he told her he believed that a woman could not win the White House in 2020.

During a debate, Sanders strongly denied having made the remark, and Warren confronted him onstage afterward, accusing him of calling her a “liar.”

Relations have been chilly since.

In her call with Biden, Warren revealed so little of her endorsement plans that a person familiar with the call remarked on her “great poker face.”