Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy is now “open” to renaming the service’s 10 bases and facilities that are named after Confederate leaders in a reversal of the service’s previous position.

Defense Secretary Mark Esper also supports the discussion, the spokesperson told POLITICO.

“The Secretary of Defense and Secretary of the Army are open to a bi-partisan discussion on the topic,” Army spokesperson Col. Sunset Belinsky said in a statement Monday.

The recent uproar over the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police drove McCarthy’s reversal, one Army official said.

The events of the past two weeks “made us start looking more at ourselves and the things that we do and how that is communicated to the force as well as the American public,” the official said.

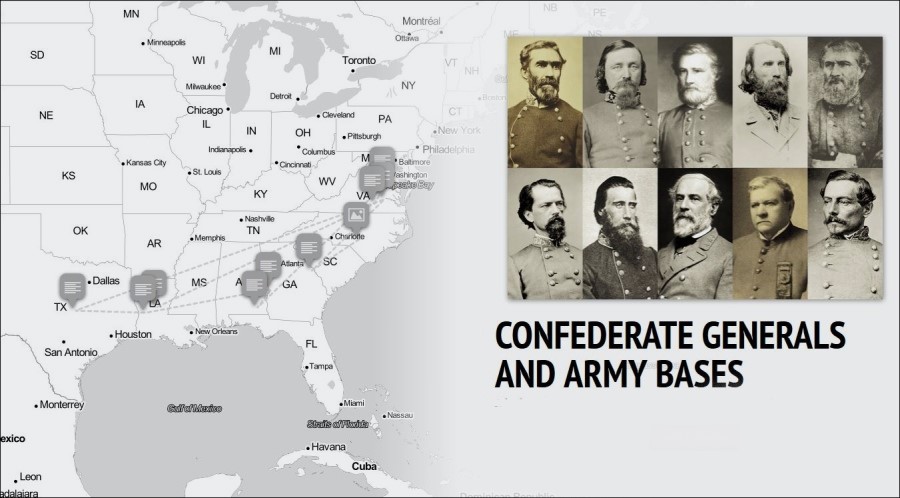

The Army operates posts named for nine Confederate generals and a colonel, including the head of its army, the reputed Georgia chief of the Ku Klux Klan and the commander whose troops fired the first shots of the Civil War.

The federal government embraced pillars of the white supremacist movement when it named military bases in the South.

Consider, for example, Fort Benning, Ga., which honors a Confederate general, Henry Lewis Benning, who devoted himself to the premise that African-Americans were not really human and could never be trusted with full citizenship.

Benning was widely influential in Southern politics and served on the Supreme Court of Georgia before turning his attentions to the cause of secession.

In a now famous speech in 1861, he told secession conventioneers in Virginia that his native state of Georgia had left the union for one reason — to “prevent the abolition of her slavery.”

Benning’s statements strongly resemble that of present-day white supremacists — and reference the race war theme put forward by the young racist who murdered nine African-Americans in Charleston five years ago.

An Army spokesperson said in February that the Army has a “tradition” of naming installations and streets after “historical figures of military significance,” including both Union and Confederate leaders.

Prior to Floyd’s death, the service was already under pressure to rename some of its best-known installations, including Fort Bragg, N.C., after a New York Times editorial accused the military of “celebrating White supremacists.”

Bragg was a major slave-owner and is largely considered to be one of the most incompetent generals of the Civil War.

The Army faces an uphill battle in renaming some or all of its 10 installations that honor Confederate military commanders.

For years, previous calls for change have gone unheeded, as officials sought to dismiss concerns by arguing the bases were named to celebrate American soldiers and that renaming them would upend tradition.

In the aftermath of violent clashes in Charlottesville, Va., over removing the town’s statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee in 2017, lawmakers called on the Army to rename two streets at Fort Hamilton, N.Y., that were named after Lee and Stonewall Jackson.

The Army refused, saying that changing the street names would be “controversial and divisive.”

The nine other Army bases in question, all in southern states, are: Forts Benning and Gordon in Georgia; Forts Pickett, A.P. Hill and Lee in Va.; Fort Polk and Camp Beauregard in Louisiana; Fort Hood, Texas; and Fort Rucker, Ala.

The unrest sweeping the country over racial injustice comes as incidents of white nationalism within the ranks appear to be on the rise.

A 2019 Military Times survey found that more than a third of troops who responded have seen evidence of white supremacist and racist ideologies in the military, a significant increase from the year before, when only 22 percent reported the same.

McCarthy signaled his evolving views in a message delivered to the force last week in response to the protests.

Following other senior military leaders who issued similar messages, McCarthy, Army Chief of Staff Gen. James McConville and Army Sergeant Major Michael Grinston acknowledged the service’s struggle with racism and pledged to do better.

“Over the past week, the country has suffered an explosion of frustration over the racial divisions that still plague us as Americans. And because your Army is a reflection of American society, those divisions live in the Army as well. We feel the frustration and anger,” they wrote. “We need to work harder to earn the trust of mothers and fathers who hesitate to hand their sons and daughters into our care.”