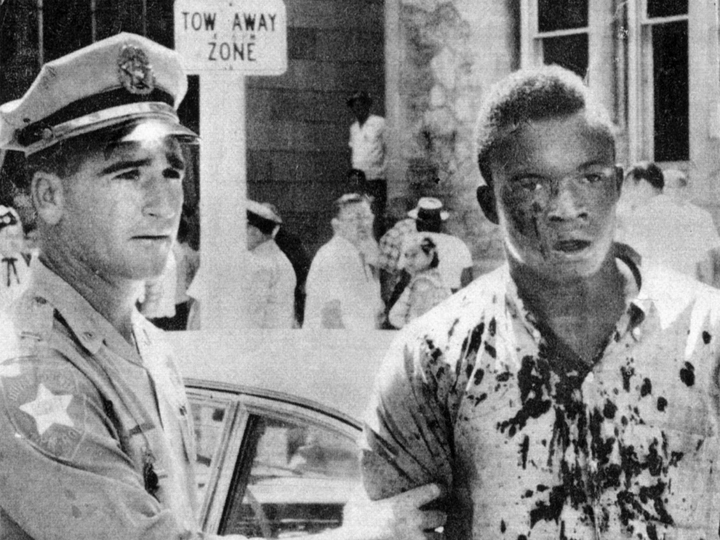

On Aug. 27, 1960, a mob of 200 white people in Jacksonville, Fla. – organized by the Ku Klux Klan and joined by some of the city’s police officers – chased and beat peaceful civil rights protesters who were trying to integrate downtown lunch counters.

The bloody carnage that followed – in which ax handles and baseball bats were used to club African Americans, who sought sanctuary in a church – is remembered as “Ax Handle Saturday.”

A permit had already been approved for the 60th anniversary commemoration of those events when Republican National Committee officials tentatively decided to move their convention festivities from Charlotte to the northern Florida city.

This happened because North Carolina public health officials resisted President Trump’s demand that they commit to allowing him to speak before a packed indoor arena amid the novel coronavirus outbreak.

Under a revised plan, which is still being finalized and has not been announced, Trump would accept his party’s nomination for a second term on Aug. 27, according to three sources familiar with the deliberations.

One venue under consideration would be the 15,000-person-capacity VyStar Veterans Memorial Arena.

Hemming Park, where local civil rights leaders have planned their commemoration, is a mile away.

This is already causing friction in the city of 900,000, which is about 30 percent black.

In 1960, Rodney Hurst was 16 and the president of the local Youth Council of the NAACP. He and several of his black high school classmates were sitting at a “whites only” lunch counter in Jacksonville when they were spit on – and then the violence began.

Now 76, Hurst is aghast at the RNC plan.

He said the commemoration event is more important than ever.

“Donald Trump is a racist,”

Hurst said in an interview Wednesday night. “To bring a racist to town for his acceptance speech will only further separate an already racially separated community.”

The RNC did not respond to a request for comment. Trump has strenuously denied that he is a racist.

The optics are messy against the backdrop of the nationwide protests and the larger cultural reckoning sparked by the Memorial Day killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis police custody.

It’s part of a pattern.

Trump told reporters on Wednesday that his first campaign rally since the start of the coronavirus pandemic will take place next Friday in Tulsa.

In 1921, that city was the site of one of the worst race massacres in U.S. history.

A white mob descended on an affluent black neighborhood.

As many as 300 people died.

The June 19 rally also happens to coincide with Juneteenth, a holiday widely celebrated in the black community to mark the day that the last American slaves were freed.

Oklahoma is not a battleground in the general election, and the county that includes Tulsa has seen an uptick in new cases since the start of June, but the state’s relaxed restrictions mean the Trump reelection campaign can assemble the big crowd that the president has been craving.

There’s another significant wrinkle as it relates to Jacksonville: One reason that the RNC gravitated toward the city is because Mayor Lenny Curry is the former chairman of the Republican Party of Florida and has been eager to host the national convention.

Early Tuesday morning, responding to protesters and calls from players for the Jacksonville Jaguars, Curry ordered the removal of the bronze statue of a Confederate soldier that since 1898 has been the centerpiece of Hemming Park.

Speaking to a crowd of Black Lives Matter activists later that day, where the “Ax Handle Saturday” commemoration is scheduled for August, the GOP mayor pledged that that he will remove all remaining Confederate monuments throughout the city, according to the Florida Times-Union.

Curry’s move presents quite the contrast with Trump, who pledged on Wednesday to block any effort to rename 10 U.S. Army bases that honor Confederate generals.

“These Monumental and very Powerful Bases have become part of a Great American Heritage, and a history of Winning, Victory, and Freedom,” Trump wrote on Twitter, naming installations in North Carolina, Texas and Georgia. “Therefore, my Administration will not even consider the renaming of these Magnificent and Fabled Military Installations.”

Trump has chosen again to use Confederate names and iconography as a wedge issue to gin up his base. He did the same amid the fallout after he declared that there were “very fine people on both sides” of the racial violence three summers ago in Charlottesville, where a counterprotester was killed by an avowed neo-Nazi who rammed his car into a crowd.

Trump’s own defense secretary, Mark Esper, said earlier this week that he would consider proposals for renaming bases.

Several of the country’s most prominent former military figures, including retired Army Gen. David Petraeus, have said doing so is long overdue.

The Marine Corps announced a ban last week on Confederate symbols in public spaces at its facilities, and Navy said earlier this week that it is moving to do the same.

Just moments after Trump’s tweetstorms defending the Confederate base names, NASCAR announced that it will ban the display of the Confederate flag from all of its events and properties.

Separately, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) called on Wednesday for the removal of Confederate statues from the U.S. Capitol.

Around 10:30 p.m. on Wednesday, protesters in Richmond toppled an iconic statue of Jefferson Davis, who was president of the Confederacy, about a half-mile down Monument Avenue from a statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee that Gov. Ralph Northam (D) is fighting in court to remove.

Back in Jacksonville, Hurst has watched the protests unfold since Floyd’s killing and wondered whether this might be the turning point that he’s been waiting for all his life.

The year before “Ax Handle Saturday,” in 1959, the city opened Nathan Bedford Forrest High School to honor the Confederate general who had become the first grand wizard of the KKK.

A few years back, they got the name changed.

Now it’s Westside High School. And he was happy to see the Confederate statue go down in his hometown this week.

“You can give some props to the mayor,” said Hurst, who previously served eight years as a Democratic member of the Jacksonville City council and wrote a book in 2018 about his experiences in the civil rights movement called “It was Never about a Hot Dog and a Coke.”

But he lamented what has not changed since that terrible day 60 years ago, and he said “the jury is still out” on whether this moment will permanently shift the public consciousness.

“Jacksonville is separated by a manmade boundary – Interstate 95 – and a natural boundary – the St. Johns River,” he said.

“Blacks live north and west of the river, and whites live east and south. There have been a few efforts here and there to change that, but none of any particular consequence. I would never use the word ‘progressive’ and Jacksonville in the same sentence. Jacksonville’s movement toward dealing with the uncomfortable subject of race in the community has been very slow. Painfully slow.”