One of Donald Trump’s favorite things to do as President has been visiting college football games in friendly locations, bathing his eternally needy ego in applause and affirmation.

Last season alone, he attended the LSU-Alabama game in November, the Army-Navy game in December, and the College Football Playoff championship between LSU and Clemson in January.

The First Football Fan was nearly as ubiquitous within the sport as Kirk Herbstreit.

That’s going to be a difficult vanity play to repeat in 2020.

There will be no college football crowds of the usual size.

There might not be college football, period.

Pessimism percolates as the time for solutions dwindles.

We are speeding in the wrong direction as a nation in terms of combating the coronavirus pandemic, and one of the cultural casualties of American casualness is an endeavor millions of us want and every college athletic department needs.

If the season dies, we know who had the biggest hand in killing any chance of it happening: Donald Trump.

When he inevitably gets around to Twitter-ranting about what has happened to the sport, Trump should instead do what he never does—accept some accountability for the state of affairs.

By blowing the summer he’s jeopardized the fall, doing more to endanger the college football season than anyone in America.

Slow to respond, quick to downplay the risk, unwilling to create a national strategy, quite willing to attack governors who took the pandemic seriously, pushing for premature openings of states, flaunting a no-mask stance for months and turning that into a belligerent political statement, Trump and his ideologues are now marinating in a midsummer mess of their own creation.

What an epic failure of leadership, one that will deprive Trump of his cherished autumn fealty festivals at a packed football stadium.

As athletic departments do their best to cloister athletes and drive down positive test counts, the spread of disease in regions around many campuses is like wildfire.

And on Thursday, the decision makers in college sports laid out the current crisis in stark terms.

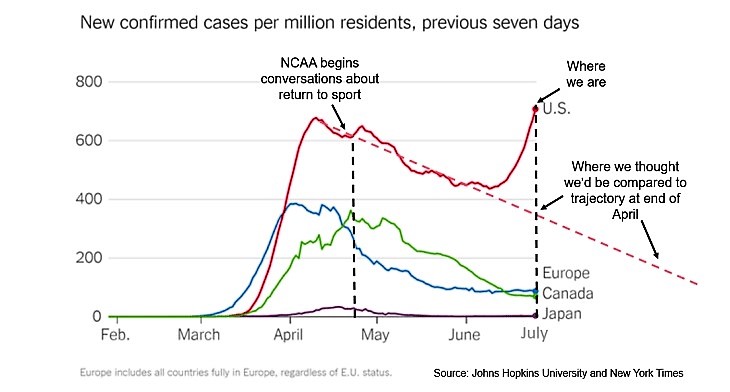

A graphic in the NCAA’s latest set of return-to-sport guidelines was a reality slap.

The graphic showed where the United States was in terms of confirmed cases in late April, when the NCAA began crafting procedures for how college athletics can resume in the fall.

It showed the projected downward trend line for where the U.S. was heading, if it sustained initiatives it had begun and reopened with commensurate pragmatism and care.

And it showed how our numbers went the other way while Europe, Canada and Japan flattened the curve.

From the NCAA report: “As the graph below indicates, when the NCAA began discussions about return of sport after the cancellation of 2020 winter and spring championships, there was an expectation that such a return would take place within a context that assumed syndromic surveillance, national testing strategies and enhanced contact tracing. Although testing and contact tracing infrastructure have expanded considerably, the variations in approach to reopening America for business and recreation have correlated with a considerable spike in cases in recent weeks. This requires that schools contemplate a holistic strategy that includes testing to return to sports with a high contact risk.”

The rest of the NCAA document, and a corresponding set of policies from the Power 5 conferences that was obtained earlier Thursday by my Sports Illustrated colleague Ross Dellenger, portray the daunting task facing college sports—and primarily football—this fall.

Crafted with the input of dozens of health experts, the two documents lay out parameters that make it difficult to envision a fall season being played without massive interruption. If it’s played at all.

Consider this, from the NCAA guidelines: “When an athlete tests positive for COVID-19, local public health officials must be notified, and contact tracing protocols must be put in place. All individuals with a high risk of exposure should be placed in quarantine for 14 days as per CDC guidance. This includes members of opposing teams after competition. The difficulty is defining individuals with a high risk of exposure, and in some cases, this could mean an entire team (or teams).”

So, this is a potential scenario as the schedule currently stands: Ohio State plays at Michigan State Oct. 17.

Afterward, a Buckeye who saw significant action in the game tests positive.

The entire team could then be subject to missing the matchup the following week at Penn State, and the Spartans could be decimated for their game the following week against Indiana.

And who knows about the week after that.

Virus spread had been sufficiently contained in some other countries to allow sports to be played, thus far without disastrous fallout.

The U.S. has lost all containment, yet still is hoping to play games.

Professional leagues are one thing—well-paid adults represented by unions are making their own choices.

College athletics, which many in America consider a raw deal for the star athletes in revenue-producing sports, are something else entirely.

Even if everything were going smoothly, the college football optics would not be great.

Things are not going smoothly in Donald Trump’s America.

From July 8-15, the average daily confirmed virus cases in the U.S. was 63,018, according to The New York Times.

That’s the highest seven-day average to date, which has added rising stress to hospitals and medical personnel in hard-hit states such as Florida, Texas and California.

But this isn’t just about caseload, which many Trump acolytes like to dismiss as immaterial.

The positivity rate is climbing, and so is the death rate.

The average death toll from July 8-15 was 726, highest it had been in a month after bottoming out at 471 earlier in July. Bad trend.

Very bad trend.

What could shut down a season?

The NCAA delves into that as well, noting the increase in COVID-19 spread and saying that “it is possible that sports, especially high contact risk sports, may not be practiced safely in some areas. In conjunction with public health officials, schools should consider pausing or discontinuing athletics activities when local circumstances warrant such consideration.” Among the factors that could end a season: “Campuswide or local community test rates that are considered unsafe by local public health officials.”

For everyone screaming that positive tests among young athletes don’t matter, health officials beg to differ.

Healthy young people do not live in a vacuum, even on a college campus.

They come in contact with many others who can be more susceptible to major health issues, up to and including death.

The caution being preached by every major conference, and the NCAA, is not politics.

It’s on advice of people who deal with this disease for a living.

Still, a perverse line of thought has percolated in some dim corners that people with a stake in the game are rooting for the virus and against college football.

The NCAA is not rooting against football.

The power conferences, having fed at the revenue trough for decades and now begging fans to wear masks, are not rooting against football.

The sports media industry, which is staring at its own economic disaster, is not rooting against football.

All those entities very much want college football. They’re also listening to experts tell them why college football is a really risky endeavor right now.

Perhaps football in the fall was always an impossible dream, but it seemed much more real in late May and early June, with America sacrificing and caseloads dropping.

Then the shallow reservoir of Trumpian forbearance ran out, and people went back to doing whatever they wanted to do, gorging on “freedom.”

And now we’ll see whether some semblance of college football can still be played.

If not, send the receipts for a lost season to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

Source: Sports Illustrated