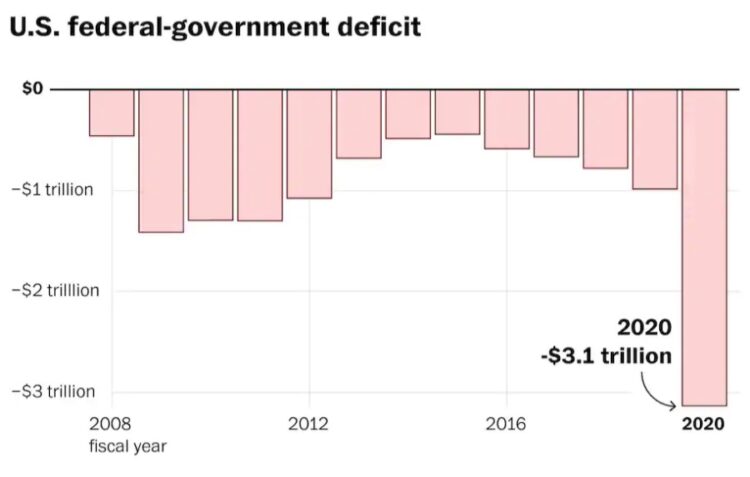

The U.S. budget deficit eclipsed $3.1 trillion in the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30, according to government data released today, by far the biggest one-year gap in U.S. history.

The data are a stark reflection of the staggering blow that the coronavirus pandemic has dealt to the U.S. economy.

The deficit — which is the gap between government spending and tax revenue — shows the dramatic surge in spending the U.S. government approved in order to contain the pandemic’s fallout earlier this year.

The deficit last year was about $1 trillion, which represented an elevated level but pales in comparison to the 2020 tally.

For 2020, the government spent $6.552 trillion, up from $4.447 trillion one year ago, according to the data released jointly by the White House and the Treasury Department.

The government brought in $3.420 trillion in tax revenue in 2020, a slight decrease from 2019.

“Most of the increase in the deficit relative to last year is higher spending as a result of covid relief,” said Marc Goldwein, a budget expert at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, which advocates for reducing the deficit.

The new figures come as the White House and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) are locked in negotiations about another round of economic relief, which could include another roughly $2 trillion in aid.

Spending like this could further add to the government’s budget deficit, but a range of economic experts from across the political spectrum, including Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome H. Powell, have said the assistance is necessary to prevent the economic recovery from flagging and keep millions from falling into poverty.

Numerous Republican lawmakers have bristled at the federal spending spree in response to the pandemic, and the surging deficit may fuel their reluctance to authorize additional relief.

Conservatives alarmed by the deficit may also push hard for its reduction should Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden win the election, setting the stage for a revival of the fierce budget battles that characterized much of the Obama administration.

The government traditionally runs some sort of budget deficit, and it finances the gap between taxes and spending by issuing debt. Interest rates are low, which has made it relatively inexpensive to issue debt.

But the debt totals have risen markedly during the Trump administration, even before the pandemic, upending his 2016 campaign vow to completely eliminate the debt over eight years.

The debt when Trump entered office was about $14.4 trillion.

It now stands at around $21 trillion.

The previous highest deficit recorded was in 2009, when it came in at $1.4 trillion.

That is less than half 2020′s tally.

In March and April, Congress approved close to $3 trillion in spending programs in response to the pandemic.

This included hundreds of billion of dollars in aid for the unemployed and small businesses, as well as $1,200 stimulus checks for millions of Americans.

The economy fell into a steep recession earlier this year as many businesses shut down and sent workers home because of the virus outbreak.

The government’s spending imbalance skyrocketed in April and June as the government’s coronavirus relief efforts were implemented and the economy cratered.

That’s because the gap between federal spending and collected tax revenue grew to unprecedented levels.

The monthly deficit jumped to $738 billion for April alone, which was a record until the monthly deficit for June came in at $864 billion.

The June deficit was bigger than the entire 12-month deficit in 2018.

Spending soared across government agencies this year. The Department of Education, for instance, spent 96 percent more than it had last fiscal year, while the Small Business Administration spent close to $600 billion more than prior years due to its implementation of the Paycheck Protection Program for small businesses hurt by the virus.

Monthly deficits have since subsided somewhat, both as the pace of new government spending slowed and the U.S. economy began to bounce back and the unemployment rate fell, resulting in greater tax revenues.

In August, the monthly federal deficit came in at $200 billion as the amount of federal spending was halved from June.

But this decrease in spending has come amid signs that the economic recovery is slowing, which has prompted the White House and some lawmakers to consider more aid.

Despite the increase of the deficit, economists and lawmakers from both sides of the political aisle have clamored for more government spending.

The unemployment rate fell from 14.7 percent in April to 7.9 percent in September, but tens of millions of Americans remain out of work and elevated jobless claims have persisted.

A federal unemployment benefit for millions has expired, and economists warn that the recovery could be stalled or setback by prematurely ending government aid programs.

America’s failure to adequately stimulate the economy helped led to an tepid recovery from the Great Recession, and lawmakers should avoid making the same mistake again, said Angela Hanks, deputy executive director of the Groundwork Collaborative, a left-leaning group.

Congress must still pass more spending to prevent people from going hungry or losing their homes, she said.

“Stacked up against questions about the debt, meaningful investments to improves people’s lives should win every time,” Hanks said. “Massive investment right now will help the economy growth overall, and if we pursue austerity people will suffer and we will have a slower, more painful recovery across the board.”

Brian Riedl, a budget analyst at the conservative-leaning Manhattan Institute, warned that America’s jobs recovery has already picked up the “low-hanging fruit” positions that were easy to bring back.

Other jobs in sectors such as the hospitality, airline, and restaurant industry will be harder to bring back, particularly as the U.S. braces for an increase in coronavirus cases during the cold winter months.

“The growth is leveling off. The economic recovery is leveling off,” Riedl said. “Which means the deficit numbers will continue to be pretty bad.”

But the bipartisan consensus that approved the big jump in spending earlier this year appears to have waned, and some Senate Republicans have signaled they are not comfortable with the big spending package that the White House is now negotiating with Pelosi.

Trump fell far short of his pledge to curb the national debt from the 2016 presidential campaign, when he argued: “We’ve got to get rid of the $19 trillion in debt.”

Trump spearheaded a Republican effort to approve $2 trillion in tax cuts in 2017, and also worked with Congress to approve large spending increases in 2018.

On Wednesday, Trump told the New York Economic Club that reducing the federal debt would be a priority of his second administration even as he urges Congress to spend more than $1.8 trillion on an additional relief package. Trump also said faster economic growth would erase the U.S. debt burden, although budget experts say spending cuts or tax hikes would be necessary to do so.

“It’s very concerning to me and we’re going to start doing that. I think you’re going to start to see tremendous growth … the growth is going to get it done,” Trump said of the rising debt. “It’s very much on my mind.”

Trump also asserted on Thursday without evidence or explanation that China would pay for the stimulus package, similar to his previous false claim that Mexico would pay for the border wall. All of the spending increases he has authorized since taking office have been financed by U.S. government funds.

The $3.1 trillion deficit reflects the 2020 fiscal year, which includes several months before the pandemic struck. Both the amount of federal spending this year and the overall deficit are record amounts in American history, senior Treasury Department officials told reporters on a phone call on Friday.