Each week, good news about vaccines or antibody treatments surfaces, offering hope that an end to the pandemic is at hand.

And yet this holiday season presents a grim reckoning.

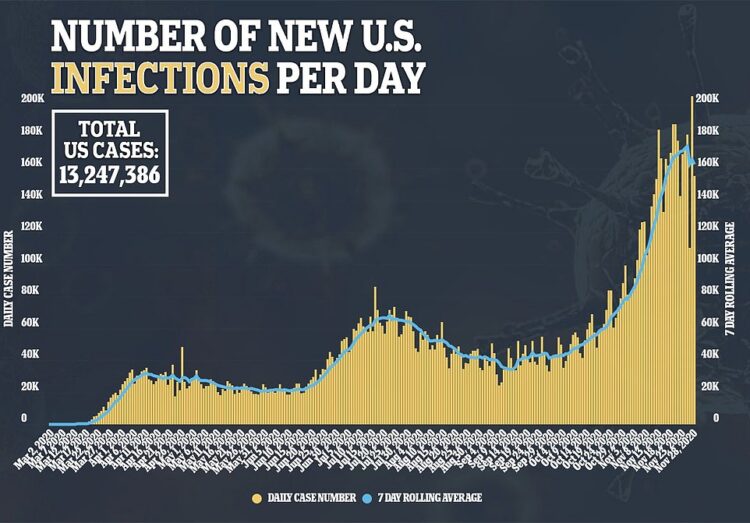

The United States has reached an appalling milestone: more than one million new coronavirus cases every week.

Hospitals in some states are full to bursting.

Since Thanksgiving, the U.S. has seen more than 500,056 new coronavirus cases, with 138,903 people testing positive yesterday.

The number of deaths is rising and seems on track to easily surpass the 2,200-a-day average in the spring, when the pandemic was concentrated in the New York metropolitan area.

Our failure to protect ourselves has caught up to us.

The nation now must endure a critical period of transition, one that threatens to last far too long, as we set aside justifiable optimism about next spring and confront the dark winter ahead.

Some epidemiologists predict that the death toll by March could be close to twice the 250,000 figure that the nation surpassed only last week.

“The next three months are going to be just horrible,” said Dr. Ashish Jha, dean of Brown University’s School of Public Health and one of two dozen experts interviewed by The New York Times about the near future.

This juncture, perhaps more than any to date, exposes the deep political divisions that have allowed the pandemic to take root and bloom, and that will determine the depth of the winter ahead.

Even as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urged Americans to avoid holiday travel and many health officials asked families to cancel big gatherings, more than six million Americans took flights during Thanksgiving week, which is about 40 percent of last year’s air traffic.

And President Trump, the one person most capable of altering the trajectory between now and spring, seems unwilling to help his successor do what must be done to save the lives of tens of thousands of Americans.

President-elect Joe Biden has assembled excellent advisers and a sensible plan for tackling the pandemic, public health experts said.

But Mitchell Warren, the founder of AVAC, an AIDS advocacy group that focuses on several diseases, said Biden’s hands appeared tied until Inauguration Day on Jan. 20: “There’s not a ton of power in being president-elect.”

By late December, the first doses of vaccine may be available to Americans, federal officials have said.

Priorities are still being set, but vaccinations are expected to go first to health care workers, nursing home residents and others at highest risk.

How long it will take to reach younger Americans depends on many factors, including how many vaccines are approved and how fast they can be made.

But even as the medical response to the virus is improving, the politics of public health remain a deeply vexing challenge.

The regions of the country now among those hit hardest by the virus — Midwestern and Mountain States and rural counties, including in the Dakotas, Iowa, Nebraska and Wyoming — are the ones that voted heavily for Trump in the recent election.

The president could help save his millions of supporters by urging them to wear masks, avoid crowds and skip holiday gatherings this year.

But that seemed unlikely to occur, many health experts said.

“That is outside of his DNA,” said Dr. William Schaffner, a preventive medicine specialist at Vanderbilt University medical school. “It would mean admitting he was wrong and Tony Fauci was right.”

In a bitter paradox, some experts noted, Trump could have been the hero of this pandemic.

Operation Warp Speed, which his administration announced in May, appears on track to deliver vaccines and therapies in record-breaking time.

The United States may well become the first country to bring the virus to heel through pharmaceutical prowess.

Had Trump heeded his medical advisers in late spring and adopted measures to curb new infections, the nation could now be on track to exit the epidemic next year with far fewer deaths per capita than many other nations.

But during his campaign, Trump rarely mentioned Operation Warp Speed; it has invested more than $12 billion in six vaccines based on three complex new technologies, as well as antibody therapies with nearly unpronounceable names like bamlanivimab.

Some health experts expressed concern that Trump might continue to undermine the coronavirus effort after he leaves office, by contradicting and diminishing any measure proposed by Biden.

“The thinking over here,” said Dr. David L. Heyman, a former C.D.C. official who now oversees the Center on Global Health Security at Chatham House in London, “is that he will continue to harass the White House to mobilize his people for 2024 for himself or his daughter or sons.”

The antidote to hopelessness is agency, and Americans can protect themselves even without Trump’s advice by wearing masks and keeping their distance from others.

Reluctant officials are finally coming around to ordering such measures.

The governors of Iowa and New Hampshire issued mask mandates for the first time in mid-November; the governors of Kansas, North Carolina and Hawaii strengthened theirs.

But average Americans are sharply divided over masks.

“There is pretty broad support for mask mandates even among Republicans,” said Martha Louise Lincoln, a medical historian at San Francisco State University. “But among extreme right-wing voters there’s still a perception that they’re a sign of weakness or a symbol of being duped.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued new guidelines on Nov. 10, advocating more clearly than before that everyone, infected or healthy, should wear a mask.

Various studies, involving machines puffing fine mists, have shown that high-quality masks can significantly reduce the spread of pathogens between people in conversation.

And the common-sense evidence that masks work has become overwhelming.

Dozens of “superspreader events” have taken place in venues where most people were not masked — in bars and restaurants, at summer camps, at funerals, on airplanes, in churches, at choir practice.

In contrast, none have been known to occur in venues where most people wore masks, such as grocery stores.

One well-known C.D.C. study showed that, even in a Springfield, Mo., hair salon where two stylists were infected, not one of the 139 customers whose hair they cut over the course of 10 days caught the disease.

A city health order had required that both the stylists and the customers be masked.

Even in the most dangerous environments — hospital emergency rooms — there have been no reported superspreader events since personal protective gear became widely available.

Many individual doctors and nurses have been infected, however; an incident in South Bend, Ind., in which multiple nurses were infected turned out to be related to a wedding.

By contrast, the White House, where masks have been shunned, has been the scene of at least one, and possibly more superspreader events.

A study by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington estimated that 130,000 lives could be saved by February if mask use became universal in the United States immediately.

Masks can also preserve the economy: A study by Goldman Sachs estimated that universal use would save $1 trillion that may be lost to business shutdowns and medical bills.

Biden has said that he intends to tackle the pandemic from his first full day in office, on Jan. 21.

But because coronavirus deaths follow new cases by some weeks, any results of his actions may not be apparent before early spring.

Source: The New York Times