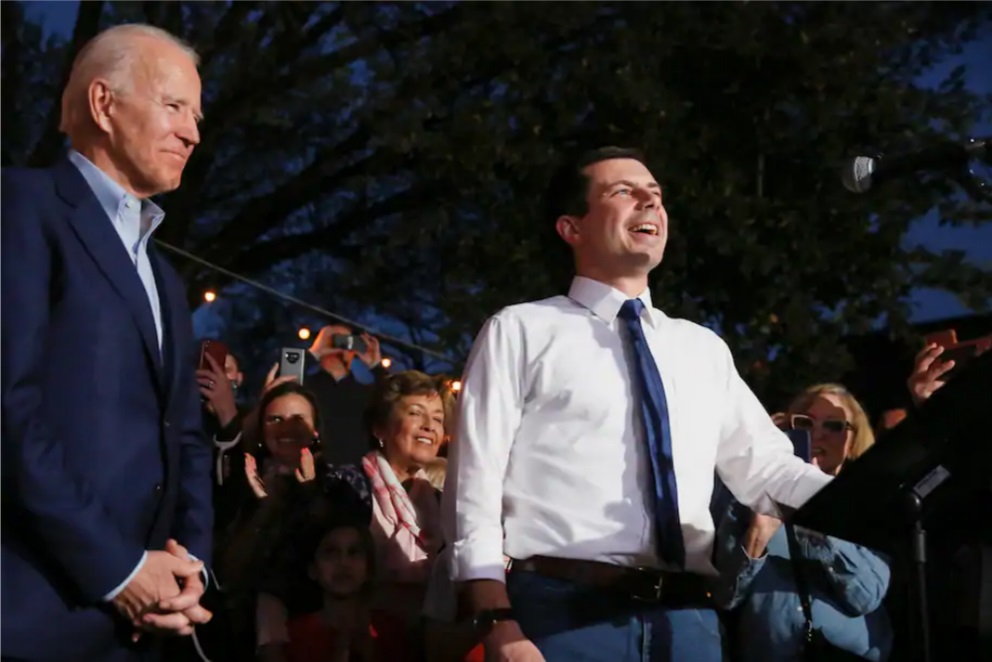

President-elect Joe Biden will nominate Pete Buttigieg to be his secretary of transportation, elevating the onetime rival to a key role in the incoming administration’s push to rebuild American infrastructure and the economy, according to three people familiar with the decision.

The former mayor of South Bend, Ind., dropped out of the presidential race and endorsed Biden at a critical moment in March ahead of the Super Tuesday primaries.

WAPO: Shortly afterward, an emotional Biden compared the former intelligence officer for the Navy Reserve, who served a tour in Afghanistan, to his son Beau, who died of brain cancer at age 46.

“It’s the highest compliment I can give any man or woman,” Biden said then, citing Buttigieg’s “moral courage” and “backbone like a ramrod,” and predicting a long and bright future. “I promise you, you’re going to end up, over your lifetime, seeing a hell of a lot more of Pete than you are of me.”

Buttigieg, 38, built his presidential bid on calls to pass the torch to a new generation of leaders, something Biden himself called “absolutely essential.”

He was the first openly gay major party candidate to win delegates in a bid for the White House, and his campaign was aided by the supportive presence of his husband, Chasten.

If confirmed, the first Washington chapter of Buttigieg’s political story will be at a vast agency long viewed as a solid, if unflashy, perch that could provide an opportunity to make a lasting mark.

Biden’s promise to pursue vast new investments in transportation and other infrastructure, while moving to sharply cut greenhouse gas emissions, will require a deft touch on questions involving technology, labor and partisanship on Capitol Hill.

Whether Buttigieg, a former Rhodes scholar and McKinsey and Co. consultant with a wonkish eye for policy but no real Washington experience, finds success in that and other challenges could play a significant role in the new president’s early successes or disappointments.

The transportation post could also provide Buttigieg with a chance to make inroads with African American voters, a slice of the population that showed little enthusiasm for his presidential bid.

He faced criticism over the shooting death of a Black man by a White police officer in South Bend, as well as questions over diversity on the city’s police force.

The top transportation job offers a chance to confront the nation’s history of constructing highways through disadvantaged neighborhoods, and what advocates say are the lasting social, economic and environmental consequences of doing so.

The transportation job will also provide a steep learning curve and sheer test of management skills. Buttigieg would oversee about 55,000 employees at the department, roughly half the population of South Bend. S

ome transportation experts have raised questions about Buttigieg’s lack of experience in the nitty-gritty, often-dense realm of federal transportation policy.

The sprawling department with a budget of almost $90 billion funds highways and transit systems, runs the air traffic control system, guarantees the safety of aircraft and airlines and regulates a trucking industry that employs millions of people.

If confirmed, one of the most pressing tasks for Buttigieg will be helping to rebuild the nation’s transportation networks, which have been battered by the coronavirus pandemic.

As passengers have stayed home and revenue has plummeted, airlines have laid of tens of thousands of employees and major transit agencies like the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority are planning deep cuts in service for the coming year.

State transportation agencies responsible for roads and bridges have projected shortfalls in the billions.

The Biden campaign has released ambitious plans to revamp the country’s transportation infrastructure — such as repairing old bridges and highways — while reducing the impact of transportation on the environment by promoting electric cars, rail and transit ridership.

Getting a big infrastructure bill through Congress would be a critical early goal for Buttigieg and the administration, but one with major pitfalls.

Republicans didn’t pass major infrastructure legislation when they controlled the House and Senate early in President Trump’s term, instead prioritizing far-reaching corporate and other tax cuts.

Depending on the outcome of two Senate races in Georgia, which will determine control of the chamber, Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) could again be in a position to block the type of ambitious infrastructure spending Biden, fellow Democrats and some Republicans argue is long overdue.

Biden has promised to repeal some Trump tax cuts to fund crucial infrastructure and other investments, but McConnell last year called that notion a “non-starter.”

Even keeping up with the status quo in federal transportation funding will be fraught for the new administration, given a deep shortfall in the Highway Trust Fund, which covers road and transit projects.

The federal gas tax, a major source of its funds, has failed to keep up with inflation and national needs, leaving many states to raise fuel taxes on their own.

Presidents Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton both signed increases in the federal gas tax, and major business leaders have pushed in recent years to raise it again.

The tax has stayed at 18.4 cents per gallon since 1993, and attempts to increase it would face strong opposition.

Within the department, Buttigieg would have broad discretion to reset priorities, which under current Secretary Elaine Chao have revolved around efforts to cut regulations — including those affecting the environment — and attempts to privatize government functions, such as air traffic control.

Some major transportation projects, undercut by Trump administration opposition, will likely be freed up to move ahead more swiftly.

For example, political leadership within the Transportation Department took pride in stymieing the Gateway Program, a series of major tunnel and bridge projects connecting New Jersey and New York.

Gateway is a priority of Senate Minority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.), with whom Trump sparred energetically despite their shared connection to New York.

Gateway’s former interim executive director, John Porcari, went on to become a Biden infrastructure adviser.

Another high priority early in the new administration will be reaching a deal with automakers on emissions standards, giving Buttigieg a role in a critical climate issue.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, part of the Transportation Department, shares the job of setting those standards with the Environmental Protection Agency. Under President Barack Obama, they were pushed upward, only for the Trump administration to roll them back.

But some auto companies agreed with California to adhere to more stringent limits, prompting a legal fight with the federal government.

Technology is also rapidly changing transportation, with NHTSA also playing a key role in the oversight of self-driving cars.

As in many areas, the Trump administration took a hands-off approach to automated vehicles, giving manufacturers latitude to conduct tests.

But safety advocacy organizations have urged the Biden administration to do more to set rules.

The department also includes the Federal Aviation Administration, whose reputation took a battering after the deadly crashes of two new 737 Max jets.

The agency recently approved design changes to the planes, certifying them as safe to fly again, but lawmakers are continuing to press for reforms.