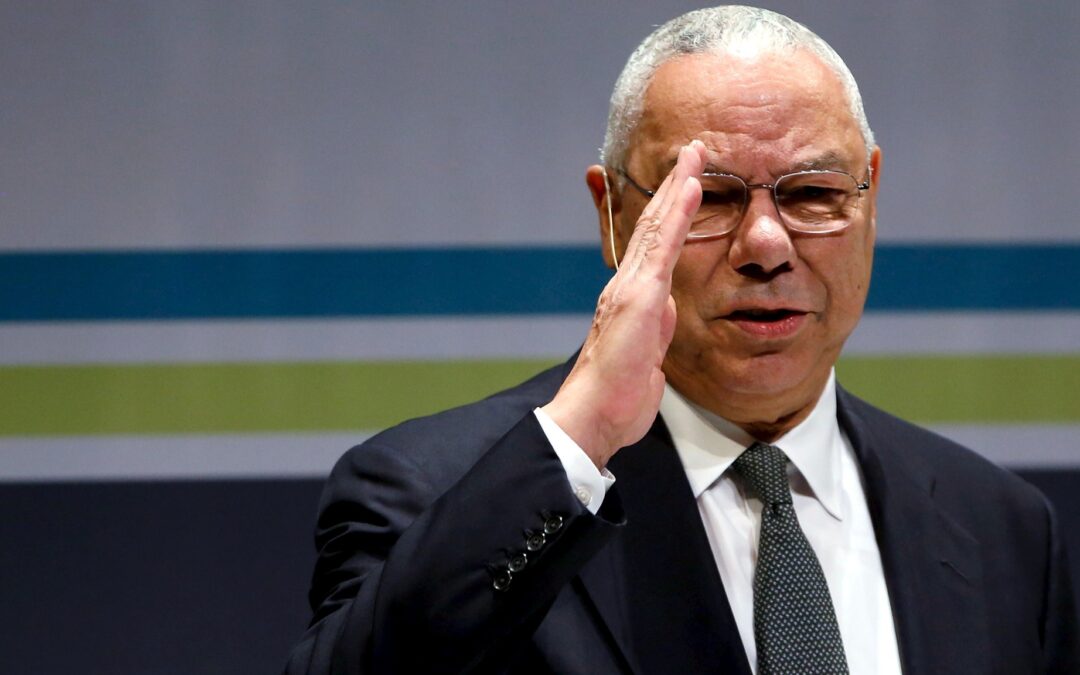

Colin Powell, who in four decades of public life served as the nation’s top soldier, diplomat and national security adviser, and whose speech at the United Nations in 2003 helped pave the way for the United States to go to war in Iraq, died on Monday.

He was 84.

The cause was complications of Covid-19, his family said in a statement, adding that he had been vaccinated and was being treated at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, in Bethesda, Md., when he died there.

A spokeswoman said his immune system had been compromised by multiple myeloma, for which he had been undergoing treatment.

He had been due to receive a booster shot for his vaccine last week, she said, but had to postpone it when he fell ill.

He had also been treated for early stages of Parkinson’s disease, she said.

Powell was a pathbreaker, serving as the country’s first Black national security adviser, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and secretary of state.

Beginning with his 35 years in the Army, Powell was emblematic of the ability of minorities to use the military as a ladder of opportunity.

His was a classic American success story.

Born in Harlem of Jamaican parents, he grew up in the South Bronx and graduated from City College of New York, joining the Army through the R.O.T.C.

Starting as a young second lieutenant commissioned in the dawn of a newly desegregated Army, Powell served two decorated combat tours in Vietnam.

He was later national security adviser to President Ronald Reagan at the end of the Cold War, helping to negotiate arms treaties and an era of cooperation with the Soviet president, Mikhail Gorbachev.

As chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Powell was the architect of the invasion of Panama in 1989 and of the Persian Gulf war in 1991, which ousted Saddam Hussein from Kuwait but left him in power in Iraq.

Along with Dick Cheney, the defense secretary at the time, Powell reshaped the American Cold War military that had stood ready at the Iron Curtain for half a century.

In doing so he stamped the Powell Doctrine on military operations: Identify clear political objectives, gain public support and use decisive and overwhelming force to defeat enemy forces.

When briefing reporters at the Pentagon at the beginning of the gulf war, Powell summed up the military’s approach: “Our strategy in going after this army is very simple,” he said. “First, we’re going to cut it off, and then we’re going to kill it.”

It was a concept that seemed less well-suited to the messy conflicts in the Balkans that came later in the 1990s and in combating terrorism in a world transformed after the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001.

By the time he retired from the military in 1993, Powell was the most popular public figure in America, owing to his straightforwardness, his leadership qualities and his ability to speak in blunt tones that Americans appreciated.

In an interview with The New York Times in 2007, he analyzed himself in the third person: “Powell is a problem-solver. He was taught as a soldier to solve problems. So he has views, but he’s not an ideologue. He has passion, but he’s not a fanatic. He’s first and foremost a problem-solver.”

Once retired, Powell, a lifelong independent while in uniform, was courted as a presidential contender by both Republicans and Democrats, becoming America’s most political general since Dwight D. Eisenhower.

He wrote a best-selling memoir, “My American Journey,” and flirted with a run for the presidency before deciding in 1995 that campaigning for office wasn’t for him.

He returned to public service in 2001 as secretary of state to President George W. Bush, whose father Powell had served as chairman of the Joint Chiefs a decade earlier.

But in the Bush administration Powell was the odd man out, fighting internally with Vice President Dick Cheney and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld for the ear of President Bush and for foreign policy dominance.

He left at the end of Bush’s first term under the cloud of the ever-worsening war in Iraq begun after 9/11 and growing questions about whether he could have, and should, have done more to object to it.

Those questions swirled in part around his U.N. speech, which was based on false intelligence, and which became the source of lifelong regret.

He kept a low profile for the next few years, but with just over two weeks left in the 2008 presidential campaign, Powell, by now a declared Republican, gave a forceful endorsement to Senator Barack Obama, a Democrat, calling him a “transformational figure.”

Powell’s backing was criticized by conservative Republicans.

But it eased the doubts among some independents, moderates and even some moderates in his own party, and largely neutralized concerns about Obama’s lack of experience to be commander in chief.

When it came time to elect Obama’s successor, Powell continued his support of Democrats, saying he would vote for Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump.

Before the election, he expressed disgust for Trump in a batch of leaked emails that a Powell spokesman confirmed as authentic.

“Trump is a national disgrace and an international pariah,” Mr. Powell wrote in one email.

Trump’s attacks on whether Obama had been born in the United States also troubled him, the emails made clear. “Yup, the whole birther movement was racist,” he said.

In the next election, he backed Joe Biden, delivering a message of support for him at the 2020 Democratic National Convention.

He is survived by his wife Alma, a son and two daughters.