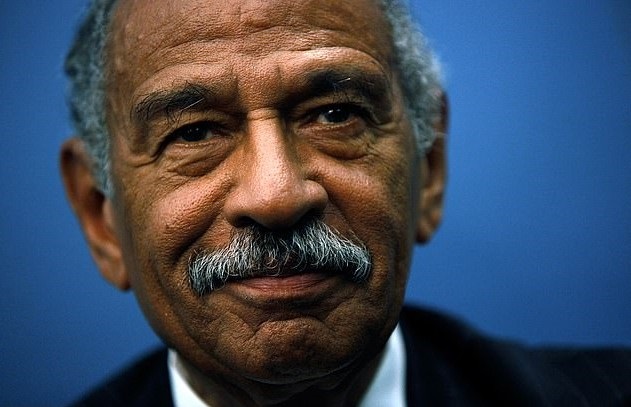

Representative John Conyers Jr., an advocate of liberal causes for five decades and the longest-serving African-American in the history of Congress, died at his home in Detroit today. He was 90.

Conyers was the only member of the House Judiciary Committee to participate in impeachment inquiries against both Presidents Richard M. Nixon and Bill Clinton.

In 1974, he said impeachment of Nixon was necessary “to restore to our government the proper balance of constitutional power and to serve notice on all future presidents that such abuse of power will never again be tolerated.”

But in 1998 he argued that Clinton’s relations with Monica Lewinsky did not merit impeachment.

Republicans, he said, “say the president has to be impeached to uphold the rule of law, but we say the president can’t be impeached without denigrating the rule of law and devaluating the standard of impeachable offenses.”

“This is not Watergate,” he added. “It is an extramarital affair.”

But he died as one of many prominent men in politics, entertainment and journalism accused of sexual misconduct, often toward employees.

Conyers resigned in 2017 after accusations of unwelcome sexual advances by two women.

His lawyers denied the accusations, but both Paul Ryan, a Republican and then the speaker of the House, and Nancy Pelosi, the House Democratic leader at the time and the current speaker, found the complaints credible and demanded that he step down.

Unlike many of the others, Conyers did not admit wrongdoing.

In fact, on the day he stepped down, he again denied that he had harassed former employees and said he did not know where the allegations came from.

MConyers was always one of the most liberal members of the House.

The liberal group Americans for Democratic Action rated his votes “liberal” 90 percent of the time over his career.

First elected in 1964 — after winning the Democratic nomination by only 108 votes — Conyers was an early critic of the Vietnam War, voting against funding it the following May. He was one of only seven representatives, all Democrats, who did.

His outspoken stands and congressional efforts tell the history of liberal causes over the last half-century.

In the 1960s he worked with Senators Edward M. Kennedy and Howard H. Baker and defeated legislation to undo Supreme Court decisions requiring congressional districts in any state to have roughly equal populations.

In 1968, only days after the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Conyers began a long and ultimately successful effort to make Dr. King’s birthday a national holiday, which was declared in 1983.

In the 1970s he began a long campaign for a government-run, single-payer system of national health insurance, and he proposed banning private ownership of handguns after assassination attempts against President Gerald R. Ford.

In the ’80s Conyers opposed the Reagan administration’s missile defense plans and its policy of “constructive engagement” with the apartheid regime in South Africa.

He criticized the death penalty and began a series of hearings on police brutality that angered New York’s mayors, Ed Koch in 1983 and Rudolph Giuliani in 1997.

But he also worked to create and enlarge federal death benefits for police officers and firefighters who died in the line of duty.

In the 1990s he opposed the Persian Gulf war and pushed legislation to study the issue of reparations for slavery.

He also challenged Janet Reno, the attorney general, over the government’s raid on the Branch Davidians religious sect at its compound in Waco, Texas, which ended with more than 70 people being killed.

Issues of race occupied, but did not preoccupy, Conyers.

He was a founder of the Congressional Black Caucus in 1971.

He opposed calls for “black power,” a movement that sought to create black institutions and make black people a political force, and instead emphasized the importance of registering and voting.

And he supported censure of the flamboyant black congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr. in 1967 for misuse of congressional funds.

The House voted to deny him his seat, overriding a recommendation from a special committee where Conyers served.

In 1967 the Supreme Court ruled that his exclusion was unconstitutional.

Later that year The Washington Post said Conyers was “emerging as the leading Negro voice in Congress and as a growing figure in Negro America.”

While there were five other black members of Congress at the time, The Post said, “only Conyers acts as though he has a constituency of 22 million Negroes.”

Conyers is survived by his wife, Monica, and sons, John and Carl.