At the end of another long shift treating coronavirus patients, Dr. Hadi Halazun opened his Facebook page to find a man insisting to him that “no one’s dying” and that the coronavirus is “fake news” drummed up by the news media.

Hadi tried to engage and explain his firsthand experience with the virus.

In reply, another user insinuated that he wasn’t a real doctor, saying pictures from his profile showing him at concerts and music festivals proved it.

“I told them: ‘I am a real doctor. There are 200 people in my hospital’s ICU,'” said Halazun, a cardiologist in New York. “And they said, ‘Give me your credentials.’ I engaged with them, and they kicked me off their wall.”

“I left work and I felt so deflated. I let it get to me.”

Halazun, like many other health care professionals, is dealing with a bombardment of misinformation and harassment from conspiracy theorists, some of whom have moved beyond posting online to pressing doctors for proof of the severity of the pandemic.

And it’s taking a toll.

Halazun said dealing with conspiracy theorists is the “second most painful thing I’ve had to deal with, other than separation of families from their loved one.”

Several other doctors shared similar experiences, saying that they regularly had to treat patients who had sought care too late because of conspiracy theories spread on social media and that social media companies have to do more to counteract the forces that spread lies for profit.

Dr. Duncan Maru, a physician and epidemiologist in Queens, New York, said he had heard from colleagues that a young patient had come into the emergency room last week with damage to his intestinal tract after having ingested bleach.

The incident occurred just days after President Trump suggested that “injection” of disinfectants should be researched as a potential coronavirus treatment.

“Folks delaying seeking care or, taking the most extreme case, somebody drinking bleach as a result of structural factors just underlines the fact that we have not protected the public from disinformation,” Maru said.

The structural factors in this case include Facebook, YouTube and Twitter, which have struggled to contain the spread of misinformation, some of it coming from positions of authority.

Social networks have taken a variety of steps in recent weeks to thwart misinformation, such as providing dedicated portals for vetted information from public health officials and banning content related to conspiracy theories around 5G wireless technology.

Despite the efforts, the distribution networks built up in recent years by fringe media personalities and activists on tech platforms and through websites have proven resilient.

Whitney Phillips, a assistant professor of communications who studies the spread of disinformation at Syracuse University, said the coronavirus outbreak offers a look at how conspiracy thinking is now, in some ways, more organized.

“With conspiracy theories, the reason they’re impervious to fact-checking is that they have become a way of being in the world for believers,” Phillips said. “It isn’t just one narrative that you can debunk. It is a holistic way of being in the world that has been reinforced by all the other bulls— that these platforms have allowed people to consume for years.”

Organized harassment campaigns, lies and urban legends targeting doctors are a real-life symptom of what the World Health Organization dubbed the “infodemic” as the coronavirus started to spread throughout the world earlier this year.

Halazun has since stopped engaging with the trolls on Facebook, some of whom claimed that “the hospitals are empty” and that the virus was part of a plot to vaccinate or microchip U.S. citizens — just two of the many conspiracy theories that have swirled around the coronavirus.

But he was still left with big questions: How can people believe this stuff? And do they understand the algorithms and opportunistic extremists that led them to believe it?

“It scares me more than anything that there are people who are basically controlled — and in the same way they feel they’re fighting against that control,” he said. “They go to YouTube, where they’re really being controlled, and they don’t realize it. That’s what’s scary.”

Maru also said he felt that tech platforms need to do more to deal with disinformation, but he acknowledged that there is no easy fix.

“I do think it’s a monumental task to hold these companies to account, but in the COVID case, they truly have blood on their hands,” Maru said.

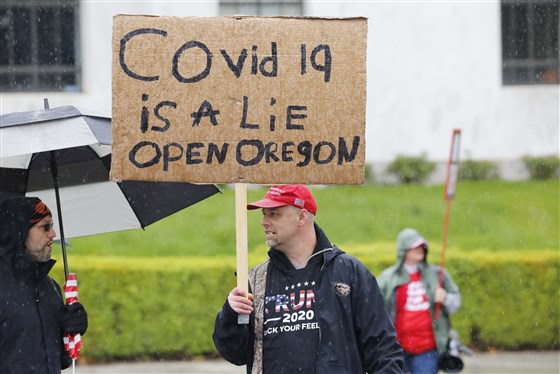

Beyond emergency rooms and internet platforms, there are hints of how far some coronavirus misinformation has spread.

Dr. Rajeev Fernando said that when he takes questions about the coronavirus on radio shows, one out of every two callers refers to 5G towers or conspiracy theories about labs in Wuhan, China.

On the phone, sometimes they’ll listen to reality, said Fernando, an infectious diseases specialist at Stony Brook Southampton Hospital in New York.

“Some people have an agenda, and you can’t help that,” Fernando said. “But for other people, I say, ‘Let me try to answer your questions and see why you think this way and why I think this is an appropriate answer.'”

Still, Fernando believes social media networks need watchdogs, including physicians, to identify disinformation before it once again becomes a public health crisis.

“We have to understand these conspiracy theorists are criminal organizations which really stop at nothing to get disinformation out,” Fernando said.

Well-organized, professional disinformation peddlers in the QAnon and anti-vaccination movements have gained new audiences during the coronavirus pandemic by coalescing around two primary boogeymen: Bill Gates and 5G towers.

Halazun heard it all firsthand. He didn’t know where it all began or how to stop it.

“These anti-vaccination people were telling me I’m a sheep,” Halazun said. “Dr. Fauci this, Bill Gates that. And I don’t really care what you think about Bill Gates. It doesn’t affect me. But it does affect me when they tell me what we’re doing is not real and that the hospitals are really empty. It hurts.”

In January, a well-known promoter of QAnon, the baseless conspiracy theory that Trump is secretly dismantling a pedophile-cannibal cabal that runs the U.S. government, pushed a conspiracy theory that Gates “patented” the coronavirus based on a mischaracterized public patent search.

The patent was created by a Gates-aligned research institute to research a vaccine, a common practice among researchers, and it covered a previous coronavirus, not the one that causes COVID-19.

Still, the tweet helped spark a focus on Gates that has permeated the various conspiracy theory networks that have developed on the internet in recent years.

The same QAnon promoter later promoted a diluted form of bleach called “Miracle Mineral Solution” as a possible way to kill the coronavirus.

Similarly, the anti-vaccination movement has pushed a false conspiracy theory that 5G towers are weakening immune systems throughout the world and that COVID-19 is a cover story for the colossal death tolls around the world.

After a prominent anti-vaccination figure posted a video on Instagram of a man alongside a destroyed 5G tower, several arson fires were set on towers across Europe and Canada.

Brian Keeley, a professor of philosophy at Pitzer College in California who studies why people believe in conspiracy theories, said some people in times of crisis look to far-fetched ideas with simple answers for complex problems.

Providing a straightforward, extinguishable enemy — whether it’s a well-known celebrity like Gates or a mysterious concept like the illuminati — gives conspiracy theorists hope, agency and power in a time of chaos.

In reality, those recognizable, often mortal figures are simply scapegoats for an act of God.

“People are looking for these kinds of explanations to control something in their lives,” Keeley said.

Keeley, who’s been researching conspiracy theories for over 20 years, said he has abandoned using Facebook because of the “depression that comes from looking at that.”

“It’s sort of an informational quarantine,” he said. “You don’t want to be exposing yourself to a different kind of virus.”

After researching why people believe in the conspiracy theories, Halazun has come to the same conclusion: Right now, it’s not worth it for a doctor to spend any time on Facebook.

“We’re limited in our emotional capacity. I’m not going to spend whatever I have left after a long day of work trying to convince a conspiracy theorist,” Halazun said. “They’re immune to any evidence. You’re not going to change their mind.”

As Halazun stepped outside after his Facebook experience, he heard the bang of pots and pans and whoops and hollers.

It was 7 p.m., and New York City residents were participating in their nightly salute to health care workers on the front lines of fighting the coronavirus pandemic.

“I just started crying,” Halazun said. “I thought, ‘What do I believe here?’ It almost made me question myself. Some people are out there who are sitting in their homes, going on these videos and then telling us it’s fake while we’re saving lives.

“I felt like ‘What are we doing this for?'”