Once ignored, underfunded and often written off, Democratic state party organizations are harvesting record-setting cash heading into the 2020 election, reasserting their roles inside the Democratic infrastructure after suffering for years in competition with super PACs and campaigns.

Across 15 possible battleground states, nearly every Democratic state party group is hitting higher quarterly fundraising totals or holding more cash on hand in their federal accounts than they did at this point during the 2016 presidential campaign, and a majority of them did both, according to a POLITICO analysis of Federal Election Commission filings and in interviews with party officials.

Many of these state parties — responsible for field operations and coordinating a ticket-wide campaign — are seeing three, four or five times the amount of cash they did before.

Those surges are happening in traditional swing states like Pennsylvania and Florida as well as emerging targets for Democrats like Texas and Arizona.

The Arizona Democratic Party raised $4.6 million in the second quarter, a more than 300 percent increase over its haul at this point in 2016, while Texas is sitting on five times more cash than it had at this point in 2016.

North Carolina banked more than doubled its 2016 totals, from $2.5 million to just under $6 million, and racked up its strong online fundraising numbers in June since late 2018.

Wisconsin, a stand out among the states, brought in a record-breaking $10 million last quarter.

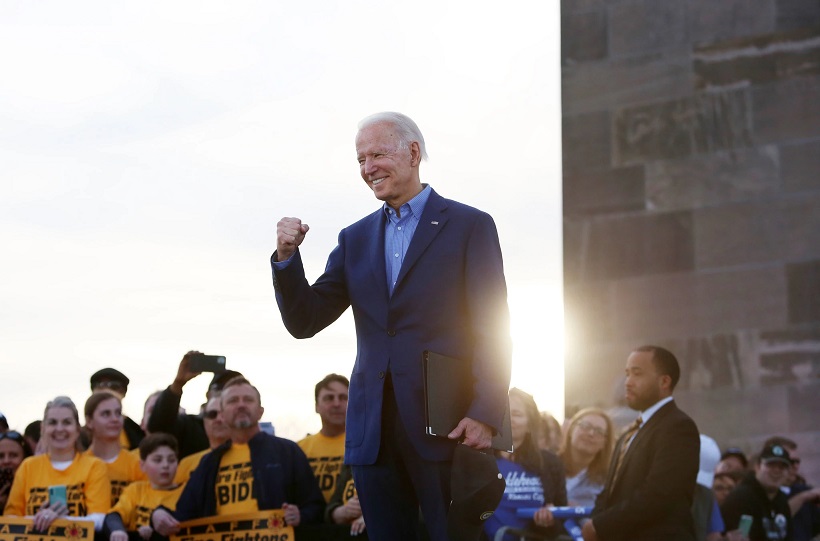

The influx of money is giving an organizing boost to Joe Biden, Senate Democrats and other candidates heading into November 2020.

Presidential candidates typically spend the final months of an election anxiously shoveling money toward state parties to fund get-out-the-vote operations and other critical infrastructure, but Democrats are running ahead of schedule this year.

That is largely thanks to donors across the country who are newly interested in funding the party’s grassroots operations as a way to combat President Trump, as well as state party leaders who have stepped up efforts to attract top donors with the promise of getting the most bang for their buck.

“A lot of donors are looking for the ‘Moneyball’ opportunity, where a dollar has the greatest possible impact,” said Ben Wikler, the Wisconsin Democratic Party chairman, citing Michael Lewis’ book about the Oakland Athletics’ pioneering data-driven approach to baseball, a style that state parties are now trying to mimic with their own pitches to top donors. “State parties may not seem sexy, but when you dig into the numbers, then they have tremendous math appeal.”

Some of the top givers in the Democratic Party — people known for writing six- or seven-figure super PAC checks — have turned state parties’ donor rolls into who’s-who lists of mega-givers from New York to California.

Alphabet Inc.’s Eric Schmidt, LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman and investor Jonathan Soros were among those donating directly to multiple state Democratic Party organizations well ahead of the 2020 election — which they did not do ahead of 2016 or 2012, federal filings show.

“There is a much more strategic giving regimen this cycle,” said Tim Lim, a Democratic digital consultant. “There’s a growing recognition that the state parties have a fundamental role to play … and all those donor advisers, donor tables talk to each other about what they’re doing and how best to spend their money.”

State parties appear to be benefiting in part from an improved relationship with the Democratic National Committee leading up to this election and, now, a nominee who is more invested in the party apparatus than President Obama was.

“For a long time, state parties were ignored during Obama’s presidency and they were incredibly weak,” said former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean, who chaired the DNC from 2005 to 2009, and described the shift of focus from the DNC and state parties to Organizing for America, the Obama campaign apparatus. “Now, they’re not [weak], which is a combination of increased competency among state parties and a donor base that’s outraged by Trump.”

Republicans, meanwhile, have also been building a strong in-state party structure for several years, investing in organizing in particular, with over 1,500 staffers on the ground in 23 targeted states.

They’ve maintained more stable data-sharing relationships in recent years, an issue which has at times proven challenging for Democrats.

“The RNC has consistently invested resources in building a strong state party system as we know it is vitally important to build the Party for years to come where we are the strongest – our grassroots and infrastructure,” Mandi Merritt, the RNC’s national press secretary, said in a statement.

Now, the growing strength of Democrats’ state party infrastructure is proving especially helpful to Biden, who largely struggled to raise money until he charged into the lead for the Democratic nomination in March.

“They came out of the primary probably with the smallest footprint of any modern-day presidential nominee,” said Ken Martin, the Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party chairman and president of the Association of State Democratic Committees. “In terms of the size and scope of the campaign, it was a very small effort, as you know. In some ways, the Biden campaign really needed to lean into the DNC and into state parties, because they needed infrastructure, and they needed it fast.”

During the entire 2016 election cycle, the 15 state Democratic parties tracked by POLITICO raised $74.3 million in federal contributions — but the vast majority of that money was doled out by centralized joint fundraising committees like Hillary Victory Fund, which allowed wealthy donors to write six-figure checks and then directed the proceeds to the Clinton campaign, the Democratic National Committee and other groups.

Individual donors acting on their own gave $13.1 million to those 15 state parties, according to FEC records.

But in 2019 and 2020, Democratic donors acting outside the party’s joint fundraising committees have already surpassed the mark from four years ago, giving $17.7 million directly to those state party organizations with three months to go until the election.

Biden’s joint fundraising efforts will pile on top of that in the coming months.

“A lot of big donors for years have invested in independent-side work and are starting to come to the realization that building out the infrastructure on the [party] side is just as important,” Martin said.

One donor adviser, granted anonymity to discuss fundraising discussions candidly, said it’s the “power of the pitch” from state parties that’s changed the dynamic, convincing big donors that their maximum $10,000 federal contributions to state parties could be more valuable than writing a bigger check to a super PAC. (Some states also have higher limits on state-level donations, or no limits at all.)

Some of those early pitches came from Kimberly Reynolds, who served as the North Carolina Democratic Party executive director from 2015 to early 2019.

Over the phone and in conference rooms in Washington, D.C., Reynolds sold donors on her party’s efforts to “Break the Majority” — ending the North Carolina GOP’s legislative supermajority in the legislature and educating donors on the state party’s role in bench-building and field operations.

Reynolds’ efforts paid off in record funds and, ultimately, a campaign that cracked the GOP’s hold on the legislature.

And she and other state party executive directors have shared their best practices with each other.

“Every discussion I have with donors focuses on what the party, and only the party, can do — building volunteer infrastructure, protecting the vote and doing year-round coalition building,” said Juan Peñalosa, executive director of the Florida Democratic Party. “Because, if the state party doesn’t have the resources to do that work, our candidates begin the race three feet behind the starting line.”

In 2019, state Democratic Party officials often pointed to their successes in the midterm elections — and likely difficult elections after 2020 — as reasons to invest.

And in Wisconsin, Democrats could also point to their coordinated victory in a state Supreme Court race earlier this year, an all-in approach to mail-in balloting that pulled out a surprise victory for Democrats.

State parties can be the hub for the “coordinated campaign,” connecting candidates up and down the ballot to resources like data-rich voter files and get-out-the-vote field operations.

“Look, we have to hustle to make our case,” said Jason Henry, executive director of the Pennsylvania Democratic Party. “And donors want to make smart investments.” Following the midterm elections, he said, “Our track record is really what we push on a lot of [donors].”

Scott Hogan, the Georgia Democratic Party executive director, noted that “there’s more money in the system, which helps all across the board, including state parties,” citing record fundraising among Democratic candidates this cycle, but the party is “the sustaining organization.”

The top expenditure line for most state parties is staff. The Georgia Democratic Party grew its paid staff from four in 2019 to 120 this month.

In Florida, they had 30 to 40 staffers ahead of the convention in 2016, but now, they’re topping out at over 200.

And in Wisconsin, staffers and volunteers knocked on twice as many doors during the 2018 cycle than during the 2016 presidential cycle.

“The one difference between our field programs in 2010 and 2014, [when we lost], compared to 2018 and 2020 is money,” said Felecia Rotellini, the Arizona Democratic Party chair, citing the party’s congressional and Senate victories in 2018. “I think donors were more comfortable giving to candidates because they knew what they were paying for, like commercials or field organizing, so we have to explain that it’s a one-stop shop with the state party.”