Donald Trump is making modest inroads with Latinos. Polls suggest he’s pulling slightly more Black support than in 2016.

But Trump is tilting at the margins with those groups.

His bigger problem is the demographic that sent him to the White House — white voters, whose embrace of Trump appears to be slipping in critical, predominantly white swing states.

In Minnesota, where the contest between Trump and Joe Biden had seemed to tighten in recent weeks — and where both candidates stumped on Friday — a CBS News/YouGov survey last week had Trump running 2 percentage points behind Biden with white voters, after carrying them by 7 points in 2016.

Even among white voters without college degrees — Trump’s base — the president was far short of the margin he put up against Hillary Clinton there.

It’s the same story in Wisconsin, where Trump won non-college educated white women by 16 percentage points four years ago but is now losing them by 9 percentage points, according to an ABC News/Washington Post poll.

In Pennsylvania, Biden has now pulled even with Trump among white voters, according to an NBC News/Marist Poll.

In 2016, white voters cast over 80 percent of the vote in each of the three states, according to exit polls.

“It’s a big, big swing,” said Lee Miringoff, director of the Marist College Institute for Public Opinion. “What [Biden’s] doing among whites is more than offsetting the slippage among non-whites … The recipe is very different this time, right now anyway, in terms of white voters.”

It’s possible that the focus on Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s replacement will help Trump, reminding voters who have drifted away from him what they cared about in 2016.

Four years ago, one in five voters — many of them white, social conservatives — said Supreme Court appointments were the most important factor in their vote.

But Trump is working from a disadvantage this year.

There are relatively few undecided voters left to persuade.

Democrats are also highly energized about the Supreme Court.

And Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the court one month before the midterm elections two year ago did nothing to stop Democrats from steamrolling Trump and the GOP.

The erosion of Trump’s white support — and its significance to the November outcome — was never more obvious than in Trump’s messaging in recent days.

Last week, he called for the creation of a commission to promote “patriotic education” while dismissing “critical race theory” and the 1619 project of The New York Times Magazine.

At a rally in Mosinee, Wis., he lit into Kamala Harris — the first major party woman of color vice presidential nominee — lamenting the possibility of her becoming president “through the back door.”

On Friday, he released a TV ad in Minnesota and Michigan lashing into Biden for supporting increased refugee admissions, including from “the most unstable, vulnerable, dangerous parts of the world.”

Then, before an overwhelmingly white crowd in Bemidji, Minn., Trump mocked Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) — the first Somali-American in Congress and a former refugee — and said Biden would “turn Minnesota into a refugee camp.”

He praised Minnesotans for their “good genes.”

But Trump’s rhetoric does not appear to be resonating with white America to the degree that he did in 2016.

That year, whites cast nearly three-quarters of the vote nationally, and Trump won those voters by about 15 percentage points, according to Pew.

Four years later, Biden has torn into that advantage, though to what degree is uncertain.

The latest Morning Consult poll showed Trump now beating Biden among white likely voters nationally by just 5 percentage points.

An NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll on Sunday put Trump up among white voters by 9 percentage points, while a PBS NewsHour/NPR/Marist poll on Friday showed Biden and Trump essentially tied with white voters.

Anywhere in that range is a problem for Trump.

It is a major reason why Biden, despite underperforming with voters of color, is still running ahead nationally.

“Suburban whites are pretty much gone” for Trump, said Ed Rendell, the former Pennsylvania governor and former chairman of the Democratic National Committee.

And Biden is far less objectionable to many working class whites than Clinton, a more polarizing nominee whose favorability ratings were lower than Biden’s.

“If Trump loses Pennsylvania by four or five points,” Rendell said, “then the suburbs and the working class whites, that accounts for the loss.”

Trump is doing better with whites in some states than others.

In North Carolina, he is drawing non-college educated white voters at about the same levels he was in 2016.

But in other states, including some with sizable populations of people of color, he is underperforming with whites.

In Florida, Trump is running ahead of Biden with white voters 56 percent to 39 percent, according to a Monmouth University poll.

But that is far short of the 32 percentage point margin he posted in 2016.

In Arizona, he has seen his 14-point edge with white voters in 2016 cut as well.

It wasn’t always clear Trump would have any problem with white voters — or that he would be making gains with people of color.

Even in the midterm elections, when suburbanites recoiled from Trump and Democrats retook the House, Republicans carried the white vote nationally by about 10 percentage points.

But white voters have not proved immune to the damage inflicted on Trump by the coronavirus and its resulting economic wreckage, which have been a drag on Trump’s reelection campaign since spring.

In particular, the pandemic appears to have hurt Trump with seniors, including older white voters concerned about both their retirement accounts and their health.

“It’s these older white voters that I think are the ones that are moving” away from Trump, said Jeff Link, a veteran Iowa-based Democratic strategist who has studied voters who turned from Barack Obama in 2012 to Trump in 2016. “The older people are like, ‘What the f— is this guy doing?’”

Earlier this year, Trump appeared to have an opening to recapture white support.

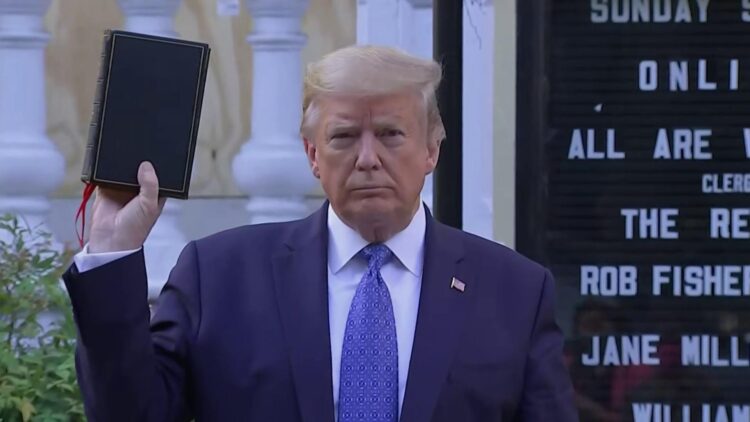

Following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis — and the ensuing protests across the country — Trump pivoted to a law-and-order campaign, with overt appeals to suburban whites.

But the effort has largely fallen flat, with numerous polls suggesting the turmoil was doing little to improve Trump’s prospects.

And the issue that motivated many white voters in 2016 — immigration, amplified by Trump’s promise to build a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border — has all but fallen out of view.

During his successful presidential campaign, 13 percent of voters ranked immigration as the most important issue facing the country.

Last month, immigration barely registered at 2 percent in Gallup’s survey of the most important problems facing the country.

Pat McCrory, the former Republican governor of North Carolina, said he has been “very surprised” that the Trump campaign has not leaned more heavily into immigration, particularly around Biden’s past statements about health care for undocumented immigrants.

But with the coronavirus and months of civil unrest on the electorate’s mind, “the two moving factors [in the election] may be the violence and the virus: The two V’s. Both parties are throwing ads and mail out on those two issues.” McCrory said, “There does seem to be a little flip” between Biden and Trump, with Biden courting working class whites and Trump “actually trying to go after the Black vote, and the Hispanic vote.”

Appearing at a town hall last week in his childhood home of Scranton, Pa., a city that is more than 80 percent white, Biden cited his “Scranton roots” in an appeal to the working class, saying he was accustomed to people deriding those “who look at us and think that we’re suckers, look at us and they think that we don’t — we’re not equivalent to them.”

Not only do public safety-based appeals appear to be faltering for Trump, white voters “still really care about pocketbook issues, and that is the underlying issue that drives their vote,” said Zak Williams, a Democratic mail strategist based in Duluth, Minn., near where Biden campaigned Friday.

“College-educated white voters were the first group that moved away from him,” Williams said, and now Trump is “starting to drive away non-college educated white voters,” too.

At the center of Trump’s re-election math has always been the expectation that he could turn out more white, non-college educated voters in 2020 than he did in 2016, squeezing more juice from a diminishing base.

Nick Trainer, the Trump campaign’s director of battleground strategy, said “the vast majority of polls are over-sampling Democrats and are relying on an outdated sampling formula.”

Trainer acknowledged Trump “has room to improve his numbers with certain voters, including suburban women and voters who disliked both candidate Trump and Hillary Clinton in 2016.”

However, he said “sustained pre-election attacks on issues we know these voters care about will hurt Joe Biden and boost President Trump.”

Even if the result is a margin of victory with non-college educated white voters that is smaller than it was four years ago, Trump will almost certainly carry that group.

And if he can turn them out in greater numbers, he could shift the electorate toward him in several predominantly white states.

Republicans and Democrats alike estimate there are hundreds of thousands of unregistered, non-college educated whites in key swing states that Trump could still pick up.

That fight for those voters was on display in Minnesota on Friday, where Trump and Biden appeared not in the Minneapolis-St. Paul suburbs, but in more culturally conservative, northern reaches of the state.

Republicans there and in some of the whitest counties in the country say they haven’t seen any fall-off for Trump, and many of them suspect that polls are still under-representing his support.

Stephanie Soucek, chairwoman of the Republican Party in Wisconsin’s Door County said she sees more Trump signs in her county than she did in 2016.

Jack Brill, acting chairman of the local Republican Party in Sarasota County, Fla., said “the base in Sarasota County is as strong as ever.”

In Duluth, the target of much attention from the Trump campaign, city’s former mayor, Gary Doty, acknowledged that the president may have shed some support among some white women because of “the way he presents himself. He’s sometimes crude and rude, and I don’t care for that style.”

However, he said, “I think there’s this silent group of people” who support Trump and will turn out for him.

Doty said that after he endorsed Trump recently, “people that wouldn’t talk to me about politics … after they heard I had supported the Trump ticket, would come say, ‘Hey, I’m for him, too.'”

Source: POLITICO