It’s the end of summer, football season is here, and the election is right around the corner.

And, oh yeah, it’s Labor Day too.

Many have forgotten the history of this holiday, but back in the late 1800s, the state of labor was grim as U.S. workers toiled under bleak conditions: 12 or more hour workdays; hazardous work environments; meager pay.

Children, some as young as 5, were often fixtures at plants and factories.

Think of that: Child labor in America.

At that time a third world country.

The dismal livelihoods fueled the formation of the country’s first labor unions, which began to organize strikes and protests and pushed employers for better hours and pay. Many of the rallies turned violent.

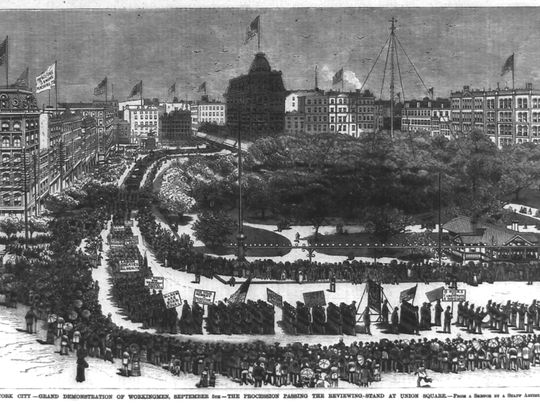

On Sept. 5, 1882 — a Tuesday — 10,000 workers took unpaid time off to march in a parade from City Hall to Union Square in New York City as a tribute to American workers.

Organized by New York’s Central Labor Union, It was the country’s first unofficial Labor Day parade.

Three years later, some city ordinances marked the first government recognition, and legislation soon followed in a number of states.

Then came May 11, 1894, and a strike that shook an Illinois town founded by George Pullman, an engineer and industrialist who created the railroad sleeping car.

The community, located on the Southside of Chicago, was designed as a “company town” in which most of the factory workers who built Pullman cars lived.

When wage cuts hit, 4,000 workers staged a strike that pitted the American Railway Union vs. the Pullman Company and the federal government.

The strike and boycott against trains triggered a nationwide transportation nightmare for freight and passenger traffic.

At its peak, the strike involved about 250,000 workers in more than 25 states.

Riots broke out in many cities; President Grover Cleveland called in Army troops to break the strikers; more than a dozen people were killed in the unrest.

After the turbulence, Congress, at the urging of Cleveland in an overture to the labor movement, passed an act on June 28, 1894, making the first Monday in September “Labor Day.”

It was now a legal holiday.

In the coming decades, the day took root in American culture as the “unofficial end of summer,” and is a reminder of the working men and women of America.